Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS)

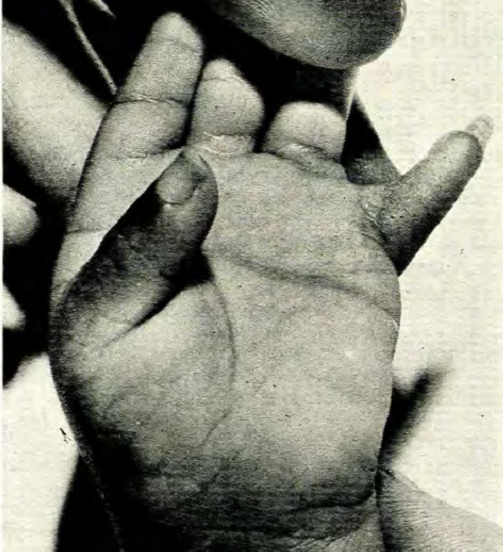

Cornelia de Lange syndrome is a member of a group of rare disorders called cohesinopathies. This term refers to conditions that affect the cohesin complex, which is involved in cell division (specifically, the separation of sister chromatids). Cohesin also has important roles in DNA repair and gene expression. Other members of the cohesinopathy group include Roberts syndrome (known since the 19th century or earlier) and Warsaw breakage syndrome (first described in 2010). Individuals with Roberts and Cornelia de Lange syndromes (CdLS) often have reduction malformations (limbs or hands/feet not fully formed). The upper limbs are mostly commonly affected in CdLS, although feet may also be affected, although some patients have very short toes. Warsaw breakage syndrome has only been reported in a handful of patients, but to date, no limb reductions have been reported.

Clinical information

Cornelia de Lange syndrome is also known as Brachmann-de Lange Syndrome. It occurs in roughly 1 person in 10,000 to 100,000 people (1-3). CdLS affects many body systems, and patients typically have intellectual disabilities and a consistent and distinctive facial appearance. As noted above, CdLS is also associated with upper limb reductions; we estimate that reductions occur in roughly 40% of patients. Other medical problems and traits associated with CdLS are as follows:

- Intellectual disability

- Microcephaly (very small head)

- Delayed speech development

- Fine and gross motor delays/disabilities

- Low birthweight/intrauterine growth retardation

- Very short stature

- Limb reductions

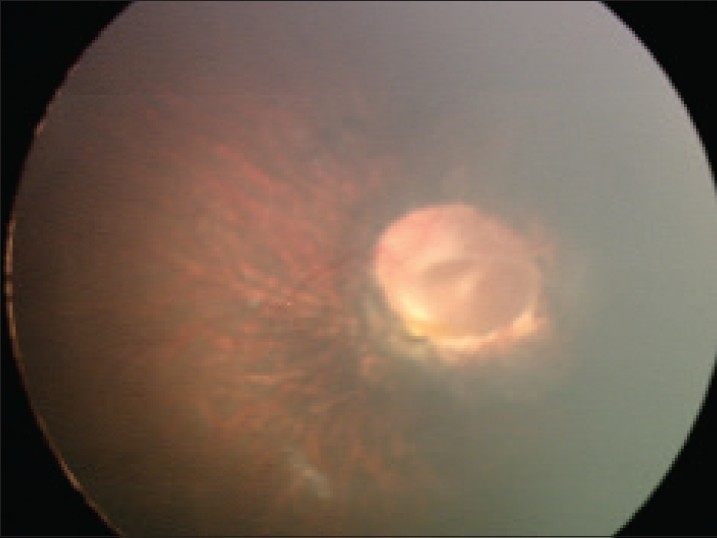

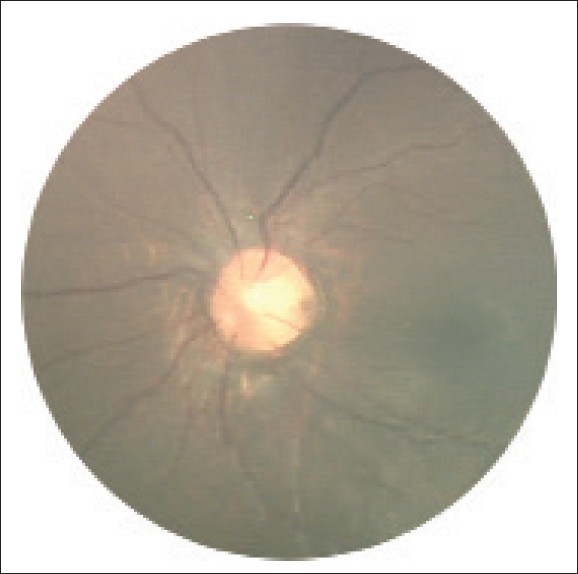

- Ophthalmological abnormalities (see photo below for example)

- Cutis marmorata (skin has areas of dilated/constricted blood vessels, giving it a red and white marbled appearance; may be more obvious when skin is cool

- Undescended testicles in boys

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Sleep disturbances

- Self-injurious behavior

- Hearing loss

- Heart problems in a small percentage of patients (<25%; atrial septal defect is most common)

Most people with CdLS live well into adulthood, although careful monitoring of health problems is very important for the maintenance of good health.

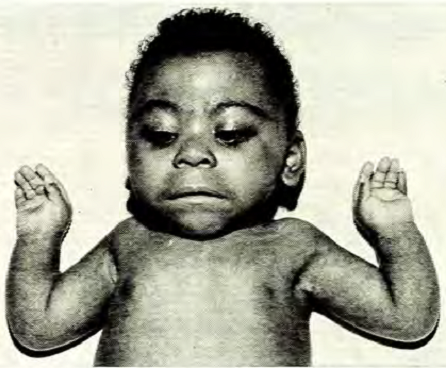

Children with CdLS often have distinctive facial features that may be noticed at birth. These features are consistent between patients of all racial and ethnic groups, although they may be relatively subtle in people who are mildly affected. Because CdLS patients share so many similarities, we have included a number of photographs on this page, as they may be helpful in diagnosis. Facial features include the following:

- Hairiness

- Synophrys (mono-eyebrow)

- Downturned mouth

- Thin upper lip

- Micrognathia (small jaw)

- Upturned nose

- Short nose

- Long philtrum (groove below nose)

- Long eyelashes

Facial characteristics of people with CdL syndrome

The phenotype of CdLS is highly variable. In general, the most severely affected patients have lowest IQs, the most severe growth retardation, and the severest limb defects. Mildly affected patients may have facial features that resemble those of more severely affected patients or they may have a less obvious set of facial features (4). They likely do not have major limb deformations. Birthweight and growth may also be normal (4). Mildly affected individuals tend to have mild to moderate intellectual disabilities, although a very small number may have IQs in the normal range. However, in spite of normal IQ, patients may still have problems in school. A review of 8 published case histories of patients with IQs in the normal range revealed that learning disabilities may occur in this group (5,6). Many, but not all, mildly affected patients have normal pre- and postnatal growth.

Researchers have found that the clinical variability seen in CdLS patients is caused by different types of gene mutations. Truncating mutations, which terminate production of a protein before it has been completely formed, result in no protein; these mutations cause more severe disease. Alternatively, missense mutations are point mutations that allow formation of a protein (which may be misshapen). These mutations are associated with milder cases (7).

Diagnosis of CdLS is usually based on the clinical characteristics outlined above. In particular, the facial features of CdLS are distinctive, consistent, and are very helpful when making a diagnosis. Along those lines, this page has a number of facial photographs of CdLS patients of different races. To aid in the diagnosis of this syndrome, clinicians and other interested individuals may wish to use the diagnostic criteria published by the Cornelia de Lange syndrome Foundation. The criteria in the file linked to here are based on a careful review of clinical and other aspects of CdLS (8).

CdLS is associated with mutations in genes: NIPBL, SMC1A, SMC3,RAD21, and HDAC8, with mutations in NIPBL being responsible for ~60% of cases (7). The way that the syndrome is inherited depends on which gene is mutated. CdLS resulting from mutations in NIPBL, SMC3, and RAD21 is autosomal dominant. This term means that only one copy of a mutated gene is enough to cause the disorder. Many autosomal dominant disorders are inherited from a parent who has the disease. Others occur when a mutation arises spontaneously (these cases are called sporadic). Both routes of transmission occur in CdLS, but sporadic cases are by far the more common route. The preponderance of sporadic cases is because the syndrome is too severe in most patients to allow for reproduction.

SMC1A- and HDAC8- related CdLS are X-linked, and account for 5% of CdLS cases each (7). The term X-linked means that CdLS is passed on when a mother passes a mutated gene located on an X chromosome to a child. X-linked conditions are usually passed from mothers to sons, with females either showing no signs of disease or only very mild signs. However, females with X-linked CdLS are the majority of patients with SMC1A CdLS. Most have the milder form of the syndrome, though severe cases have been reported (9).

In X-linked CdLS cases, the mother may be a carrier and does not show signs of CdLS, or she may have milder signs of CdLS than her offspring (see reference 10 for an example). Alternatively, the mother may have germline mosaicism. In the case of CdLS, this term means that the mutation is present in a portion of the mother's egg cells. In this situation, the mother will not have any signs of disease, and she will typically not be aware that she carries the mutation until a child with CdLS is born.

The differential diagnosis for CdLS includes fetal alchohol syndrome (FAS). Infants and children with FAS share certain features with CdLS patients, including a smooth philtrum, an upturned nose, thin upper lips, and hairiness. People with FAS also have intellectual disabilities and growth abnormalities including intrauterine growth retardation. They may also have congenital heart problems. However, the overall facial appearance of people with CdLS is distinctive, and no history of alcohol use during a pregnancy can rule out FAS.

Roberts syndrome (RS) and Warsaw breakage syndrome are two other cohesinopathies. Their phenotypes do not have a strong resemblance to CdLS. For example, RS patients are born with abnormalities/reductions in all limbs (11). Arms are usually affected most severely. RS patients may have proptosis/exophthalmos (protruding eyes) due to shallow orbits. Exophthalmos has been reported in CdLS, but it appears to be a rare problem in that syndrome. Similarities to CdLS include cleft lip or palate, which occurs more often in RS than it does in CdLS, genital abnormalities, intellectual disabilities, microcephaly, and hearing loss, among other problems. The results of cytogenetic testing are similar, but not identical, in CdLS and RS. Readers who wish to read information on this subject should consult reference 11.

RS is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the gene ESCO2. The term autosomal recessive means that the syndrome is passed on when both parents contribute a copy of the mutated gene to their child. The parents of a child with RS do not show any signs of disease. A very small number of parents of CdLS patients also show signs of the syndrome.

Warsaw breakage syndrome (WBS) was first described in 2010 (12). To date, only 5 patients have been described. None of them have the distinctive features of CdLS, including limb reductions, hairiness, and its distinctive facial appearance. WBS is caused by mutations in the gene DDX11.

Other conditions in the differential diagnosis of CdLS are Fryns syndrome, dup(3q) syndrome, and chromosome 2q31 deletion syndrome. These conditions are described in the GeneReview linked to at the right.

Growth curves for Cornelia de Lange syndrome

Children with CdLS tend to be proportionately small (that is, small all over rather than just having a small head or short legs). They are generally small at birth and by early childhood, height and head circumference are below the 5th percentile (8). A study published in 1993 measured growth in 277 children with Cornelia de Lange syndrome (13). Data was obtained from birth to age 22 years. That study found that average height in men with CdLS was ~156 cm (just over 5 feet tall). Women averaged ~131 cm (roughly 4 feet, 4 inches). The paper is freely available on the publisher's site (13); Figures 1-10 are curves of head circumference, weight, and height in girls and boys.

These growth charts are also available on the Cornelia de Lange Syndrome Foundation's website:

References

- 1. Pearce PM & Pitt DB (1967) Six cases of de Lange's syndrome; parental consanguinity in two. Med J Aust. 1(10):502-506. No abstract available.

- 2. Opitz JM (1985) The Brachmann-de Lange syndrome. Am J Med Genet 22(1):89-102. No abstract available; page 1 available from publisher.

- 3. Barisic I et al. (2008) EUROCAT Working Group; Descriptive epidemiology of Cornelia de Lange syndrome in Europe. Am J Med Genet Part A 146A(1):51-59. Abstract on PubMed.

- 4. Deardorff MA et al. (2007) Mutations in cohesin complex members SMC3 and SMC1A cause a mild variant of Cornelia de Lange syndrome with predominant mental retardation. Hum Mutat 34(12):1589-1596. Full text on PubMed.

- 5. Saal HM et al. (1993) Brachmann-de Lange syndrome with normal IQ. Am J Med Genet 47(7):995-998. Abstract on PubMed.

- 6. Kline AD et al. (2007) Natural History of Aging in Cornelia de Lange Syndrome. Am J Med Genet C 145C(3):248-260. Abstract on PubMed.

- 7. Mannini L et al. (2013) Mutation spectrum and genotype-phenotype correlation in Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Hum Mutat 34(12):1589-1596. Full text on PubMed.

- 8. Kline AD et al. (2007) Research review Cornelia de Lange syndrome: clinical review, diagnostic and scoring systems, and anticipatory guidance. Am J Med Genet Part A 143A(12):1287-1296. Abstract on PubMed.

- 9. Hoppman-Chaney MA et al. (2012) In-frame multi-exon deletion of SMC1A in a severely affected female with Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A 158A(1):193-198. Abstract on PubMed.

- 10. Robinson LK et al. (1985) Brachmann-de Lange syndrome: evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance. Am J Med Genet Part 22(1):109-115. Abstract on PubMed.

- 11. Gordillo M et al (2006) Roberts Syndrome. Updated November 14, 2013. GeneReviews [Internet] Pagon RA et al., editors. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2021. Full text.

- 12. van der Lelij P et al (2010) Warsaw breakage syndrome, a cohesinopathy associated with mutations in the XPD helicase family member DDX11/ChlR1. Am J Hum Genet. 86(2):262-266. Full text on PubMed.

- 13. Kline AD et al. (1993) Growth manifestations in the Brachmann-de Lange syndrome. Am J Med Genet 47(7):1042-1049. Abstract on PubMed. Full text from publisher.

- 14. Cicoria A (1974) Brachmann-de Lange Syndrome. A report of two cases. S Afr Med J 48(21):919-921. Abstract on PubMed.

- 15. Begeman G & Duggan R (1976) The Cornelia de Lange Syndrome. A Study of 9 Affected Individuals. S Afr Med J 50(38):1475-1478. Abstract on PubMed.

- 16. Wierzba J et al (2012) Cornelia de Lange syndrome with NIPBL mutation and mosaic Turner syndrome in the same individual. BMC Med Genet 13:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-43. Full text on PubMed.

- 17. Shenoy BH et al. (2014) Cornelia de Lange syndrome with optic disk pit: Novel association and review of literature. Oman J Ophthalmol 7(2):69-71. Full text on PubMed.