Kyphoscoliotic Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (kEDS)

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS) are a group of 13 related conditions that affect connective tissue (1). Connective tissue is found everywhere in the body. It connects other types of tissues, separates them, and supports them. Examples of connective tissue include bone, cartilage, fat, blood, and lymphatic tissue. When connective tissue is abnormal because of a disease, a variety of problems result.

For example, certain problems happen in all of forms of EDS. The first is joint hypermobility (often called loose or double joints). People with EDS can often move their joints in ways that are impossible for most unaffected people. The photograph at the bottom of this page has an example (note that many people without EDS have loose joints, so having joint hypermobility does not mean that you have EDS). The second thing that happens in every type of EDS is stretchy (hyperextensible) skin. This feature is nearly universal in some types of EDS (such as type 1, the classical form). In our literature survey, we found that stretchy skin occured in less than half of people with the hypermobile and vascular forms, more than half of patients with the periodontitis type, and in a large majority of people with the arthrochalasia type (>80%).

Many forms of EDS happen because of mutations in genes that make collagen, which can be thought of as both holding the body together and strengthening it. Collagen gives structure to muscles, tendons, skin and bones. In most people, it is abundant in these tissues. In people with EDS, collagen may not be as strong as it should be, or there may not be enough of it. For example, skin and joints may be loose because they don't have enough collagen to hold them together securely, or because the collagen they have is weaker than it should be.

Doctors and other medical professionals assess joint hypermobility with a scoring system called the Beighton score, which was developed in the early 1970s (2). This simple system scores your ability to move a joint past certain angles. The highest score is 9 points, and higher scores mean greater joint hypermobility. Generally speaking, scores of 4 or higher (at any time, past or present) indicate joint hypermobility. Many EDS patients have scores of 8 or 9, although many have lower scores, and a minority do not have hypermobile joints. Interested readers may wish to see a basic description of the scale with a video and photos or a more technical description.

Joint hypermobility puts EDS patients at high risk for joint dislocations and partial dislocations (called subluxations). These problems can be painful, and in some cases, debilitating. Surgical procedures have been used to improve skeletal stability and improve quality of life; for examples and reviews, see references 3-5. However, experts tend to agree that non-surgical options should always be exhausted first, and careful discussions with doctors are important in this decision.

Tissue fragility is another common feature of EDS. This problem is very serious in the vascular type of EDS (vEDS). The type of collagen affected in vEDS plays a role in supporting blood vessels. When the integrity of their support system is affected, blood vessels can rupture spontaneously. This problem is especially dangerous because it affects medium and large blood vessels, as well as small ones. It also affects the bowel. Surgery on a person with vEDS must be performed with great care in order to avoid serious complications. This problem may also happen in kyphoscoliotic EDS (kEDS), but it is less common than in vEDS. Alternatively, while people with the hypermobile form (hEDS) are also prone to blood vessel ruptures, ruptures tend to occur in the small blood vessels. Tissue fragility can also lead to hernias and problems in pregnancy. Fragile skin is also a common manifestation of EDS, especially in people with the classic, kyphoscoliotic, and periodontitis types.

Tissue fragility in EDS can also lead to hernias and problems in pregnancy. Fragile skin is also a common manifestation of EDS, especially in people with the classic, kyphoscoliotic, and periodontitis types.

A new classification system for EDS was released in 2017 (1). It's called the 2017 International Classfication for the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes. This new system names 13 different subtypes of EDS. It relies primarily on descriptive terms for different types of EDS (e.g. vascular EDS, meaning that it affects blood vessels prominently). Two other systems existed before this one. They were named Villefanche [1998] and Berlin [1988]. Both systems used names and numbers. The numbers in the new system are different from the old ones, and we've included the old ones here. Advances in genetics have allowed to researchers to find genes that cause different subtypes of EDS, which has allowed them to separate the old classic subtype (numbered 1 & 2) of EDS into 2 different subtypes.

- 1. Classical EDS (cEDS; formerly type 1/2)

- 2. Classical-like EDS (cEDS; formerly type 1/2)

- 3. Cardiac-valvular (cvEDS)

- 4. Vascular (vEDS)

- 5. Hypermobile (hEDS; formerly type 3)

- 6. Arthrochalasia (aEDS; formerly type 7a/b)

- 7. Dermatosparaxis (dEDS; formerly type 7c)

- 8. Kyphoscoliotic (kEDS; formerly type 6)

- 9. Brittle Cornea syndrome (BCS)

- 10. Spondylodysplastic (spEDS)

- 11. Musculocontractural (mcEDS)1

- 12. Myopathic (mEDS); type 12

- 13. Periodontal (pEDS; formerly type 8)

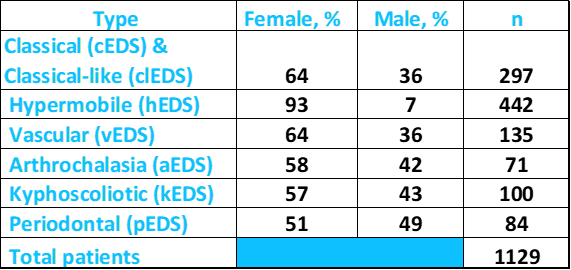

EDS affects women more commonly than men. In the literature survey we did for our analytics tool, we counted the number of male and female patients while we were characterizing in six different types of EDS. Altogether, we analyzed data from ~1,200 patients. Sex information was available for ~1,100. The table below shows that although more EDS patients are women in each type of EDS, the female:male ratio varied between each type. For example, females dominated the individuals reported with the hypermobility type, while males comprised a substantial minority of kyphoscoliotic and arthrochalasia patients. The distribution was roughly even in the periodontal type. However, the low number of case reports for these three types of EDS may have affected the outcome of this small analysis.

Above: Percentages of male and female patients with different types of EDS. Source: FDRF via published literature.

According to NIH's Genetics Home Reference (see link at right), the prevalence of all forms of EDS is roughly 1 in 5,000 worldwide. The kyphoscoliotic type (kEDS) is very rare, and although exact figures are not known, the GeneReviews article at the right estimates that it occurs in one birth per 100,000.

Clinical information:kEDS

The most striking feature of kEDS is kyphoscoliosis. This term means that patients have both kyphosis (a front to back curve of the upper spine) and scoliosis (an s-type curve of the back). This problem is often present at birth and otherwise tends to develop at early ages. It often progresses to a point of striking severity (see photos). In addition, kEDS patients may have distinct facial features, such as wide-set eyes or eyes that slant downward.

The most common clinical featuers of kEDS are as follows. For a list of problems used to diagnose kEDS, see the Diagnosis and Testing section below.

- Kyphoscoliosis that tends to get worse with time (front to back and s-shaped curves of the spine)

- Joint laxity/hypermobility (joints can be easily moved into relatively extreme positions)

- Hyperelastic/stretchy skin that appears normal after being released

- Severe neonatal muscular hypotonia (floppiness of muscles)

- Delays in motor development (e.g. late walking)

- Joint dislocations or subluxations

- Wrist drop in infancy (see photo)

- Blue sclerae (see photo below)

- Flat feet and/or clubfeet

- Skin that bruises easily

- Myopia/nearsightedness

- Smooth, velvety skin

- Sunken chest

- Osteopenia

- Hearing loss

- Small corneas

- Glaucoma

- Weakness, including a weak cry as an infant

Common clinical features of kEDS

In addition, a minority of kEDS patients have intellectual disabilities. Fragile/ruptured blood vessels also occur in a minority of kEDS patients. Readers may wish to consult a review about kEDS that contains descriptions of 15 patients (6) or another that describes 17 and has many photos (9).

Diagnosis and Testing

kEDS is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations the gene PLOD1 or IN FKBP14. The term autosomal recessive means that a mutated copy of the gene must be inherited from each parent. PLOD1 codes for the enzyme lysyl hydroxylase 1, which is important for collagen formation and stabilization. Gene sequencing can confirm the diagnosis, as can an assay of lysyl hydroxylase activity in skin fibroblasts. Alternatively, there is also a urine test that uses high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). This test looks for an increased ratio of deoxypyridinoline to pyridinoline crosslinks and may be relatively inexpensive compared to sequencing, and is non-invasive compared to a skin biopsy for the enzyme assay. For a list of labs that perform testing, see the links at right.

FKBP14 codes for a structural protein named FKBP prolyl isomerase 14. This protein appears to help with procollagen folding. Procollagens are prescursors to collagens.

The criteria below were established as part of the 2017 classification system (1). For a diagnosis, a patient must have the first two major criteria as well as EITHER the third major criterion OR three of the minor criteria. Identification of a mutation is also essential. Gene-specific minor criteria are listed below. Laboratory testing for deoxypyridinoline and pyridinoline ratios in urine is a sensitive test for kEDS caused by the gene PLOD1 (see below). This test may be called an LP/HP ratio or Dpyr/Pyr ratio. See reference 1 for more information.

Major criteria

- Congential muscle hypotonia (floppiness of muscles at birth)

- Congenital or early onset kyphoscoliosis; progressive or nonprogressive (back curvature that may or may not get worse with time)

- Joint hypermobility with dislocations and subluxations (partial dislocations)

Minor criteria

- Hyperelastic/stretchy skin

- Easily bruised skin

- Rupture/aneurysm of a medium-sized artery

- Osteopenia/osteoporosis (low bone density)

- Blue sclerae (whites of the eyes are blue or blue-ish)

- Hernia (umbilical or inguinal)

- Pectus deformity (a chest deformity, often a "sunken chest")

- Marfanoid habitus (tall, slender body type with long, slender fingers)

- Talipes equinovarus (clubfoot)

- Refractive errors (myopia, hypermetropia; near- or farsightedness)

Certain features of kEDS differ depending on which gene is mutated:

- Fragile skin (easy bruising, friable skin, poor wound healing, wide atrophic scars)

- Scleral and ocular fragility/rupture

- Microcornea (the cornea of the eye is smaller than usual)

- Facial dysmorphology (low-set ears, epicanthal folds, down-slanting palpebral fissures [down-slanting eyes], synophrys [mono eyebrow], and high palate)

- Hearing loss at birth

- Follicular hyperkeratosis (rough, cone-shaped, elevated papules on the skin)

- Muscle atrophy

- Bladder diverticula

Differential Diagnosis

Other forms of EDS.The differential diagnosis for kEDS includes all the other forms of EDS. The spondylodysplastic form (spEDS) shares many similarities with kEDS. In this condition, lysyl hydroxylase activity (see previous section) is normal. Additionally, kEDS overlaps with the vascular (type 4) and classic (types 1 and 2) forms of EDS. Laboratory testing can give a definitive diagnosis of kEDS. However, clinically, scoliosis in kEDS tends to be more severe than it is in the other forms and its onset is usually earlier than in the vascular and classic forms.

Brittle cornea syndrome (BCS). BCS is another connective tissue disorder that was classified as a subtype of EDS in 2017 (1). BCS patients often suffer corneal ruptures after minor eye trauma and corneal degeneration (keratoconus). Like other EDS patients and kEDS patients in particular, they may also have blue sclerae, joint hypermobility, hyperelastic skin, and hearing loss. Laboratory and genetic testing can distinguish kEDS from BCS.

Cutis laxa. Superficially, the stretchy skin found in most forms of EDS may be confused with cutis laxa type 1 and type 2, as stretchy skin is also a feature of these conditions. However, the skin in cutis laxa patients tends to sag and does not return to its normal position after being extended. Cutis Laxa patients often have a prematurely aged appearance.

A number of congenital muscle disorders feature hypotonia, and kEDS may be confused with them in very young patients. These disorders include X-linked myotubular myopathy and spinal muscular atrophy. The velvety skin and striking joint hypermobility in kEDS may help distinguish these other disorders from one another. In addition, deep tendon reflexes are abnormal in the muscle disorders, but are normal in kEDS.

References

- 1. Malfait F et al. (2017) The 2017 International Classification of the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes Am J Med Genet C 175(1):8-26. Abstract on PubMed.

- 2. Beighton P et al. (1973) Articular mobility in an African population. Ann Rheum Dis 32(5):413-418. Full text on PubMed.

- 3. Cole AS et al. (2000) Recurrent instability of the elbow in the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. A report of three cases and a new technique of surgical stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 82(5):702-704. Full text from publisher.

- 4. Weinberg J et al. (1999) Joint surgery in Ehlers-Danlos patients: results of a survey. Am J Orthop 28(7):406-409. Abstract on PubMed.

- 5. Shirley ED et al. (2012) Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in orthopaedics. Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment implications. Sports Health 4(5):394-403. Full text on PubMed.

- 6. Rohrbach M et al. (2011) Phenotypic variability of the kyphoscoliotic type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS VIA): clinical, molecular and biochemical delineation. Orphanet J Rare Dis 6:46. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-46. Full text on PubMed.

- 7. Kariminejad A et al. (2010) Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VI in a 17-year-old Iranian boy with severe muscular weakness - a diagnostic challenge? Iran J Pediatr 20(3):358-362. Full text on PubMed.

- 8. Canpolat M et al. (2014) Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Type VI: A case report. Turk J Pediatr Dis 2:101-104. Full text from publisher (click on EN tab for English).

- 9. SamuelEDS94 (2013) Photograph on the Wikimedia Commons.

- 10. Giunta C et al. (2018) A cohort of 17 patients with kyphoscoliotic Ehlers-Danlos syndrome caused by biallelic mutations in FKBP14: expansion of the clinical and mutational spectrum and description of the natural history Genet Med 20(1):42-54. Full text on PubMed.

_phalangeal_joints_Cropped.jpg)