Fanconi Anemia (FA)

Fanconi anemia, or FA, is is an inherited disease that causes abnormalities of the blood and skeleton. Patients also often have abnormalities of growth and development. All people with FA are prone to getting cancer.

FA has been classified as a member of different groups of diseases. One of them is the DNA repair disorders. Patients with these disorders have problems in fixing damaged DNA. DNA is constantly damaged by a variety of agents including ultraviolet light from the sun, flourescent lights, and other sources, ionizing radiation from the cosmos, X-ray equipment and other medical devices, chemicals, normal internal processes in cells, and other substances or processes. Damage to DNA is constant, and living things have evolved many systems for fixing it. For example, there are proteins that recognize that it is damaged, enzymes that remove damaged areas, other enzymes that unzip a strand of DNA so that other molecules can get enter and make repairs, and enzymes that insert new, undamaged DNA bases. This list is not exhaustive. When a person has a defect in one of these repair systems, disease results. Overall, DNA repair disorders greatly increase the risk of cancer.

FA is also a chromosome breakage disorder. Chromosomes are bundles of DNA that cells make to package DNA into compact structures. The This chromosome breakage disorder means that chromosomes are unstable and/or prone to breaking. Patients with these disorders have defects in systems that repair damaged chromosomes. Other diseases in this group include Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome (NBS), ataxia-telangiectasia, and Bloom syndrome.

FA is a rare disease, but it is a common cause of other conditions like aplastic anemia and blood-based malignancies. Its prevalence has been estimated for different groups around the world with varying results. For example, its prevalence in black South Africans has been estimated as roughly 1 person in 476,000 (1), while another estimated that it occurred in 1 black person in 40,000 in Bantu-speaking populations in sub-Saharan Africa (2). Alternatively, prevalence has been estimated at 1 person in 22,000 Afrikaaner South Africans (3). Prevalence is as high as 1 person in 40,000 in Israelis (4).

The information on this page is only a summary of the clinical features of FA. The Fanconi Anemia Research Fund has produced an extensive manual on diagnosing FA and managing it. This book is freely available and is highly recommended.

Clinical information

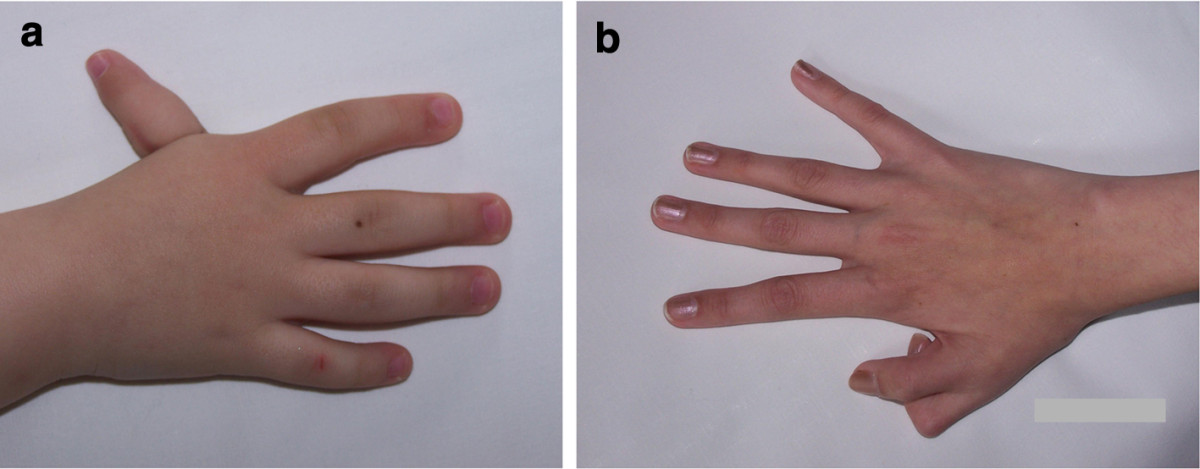

Two key features of FA are malformations that are present at birth and low levels of certain blood cells. These malformations can occur in many body systems (skeleton, kidneys, eyes, ears, genitalia, and the central nervous system). The thumbs are commonly affected. FA patients may have extra or missing thumbs, thumbs that are slightly out of place, or other structural abnormalities.

Blood cells are also affected in FA. For example, low platelet counts are universal or nearly so, though the problem may not be present at birth. In many patients, these problems may not become evident until ages 4 to 7. Blood cell problems are not limited to platelets. A large number of FA patients have low white and red cell counts as well. When all three of these problems are present, a person is described as having pancytopenia, or a deficiency of all three cellular components of the blood. Pancytopenia can cause many problems. One is anemia (results from too few red cells). Red blood cells transport oxygen to all the body's cells and tissues. People with anemia do have provide enough oxygen to their tissues. As a result, they feel tired, have low energy levels, and often look pale. FA patients may also have too few white blood cells, making it harder for them to fight infections. Low platelets make them prone to bruising and bleeding. Blood transfusions can help these problems. Overall in FA, low blood cell counts result from poor function of the bone marrow, where blood cells are made.

The clinical features of FA vary from patient to patient. A few patients may have nearly all the features associated with FA. Some may have some or no congenital malformations. Alternatively, some may have problems that are not generally associated with FA. These facts complicate diagnosis.

Some common signs and symptoms of FA are listed below.

- Low energy/easy fatiguability (patients may become breathless with minimal effort)

- Pancytopenia (low RBCs or hemoglobin, low white cell and platelet counts)

- Bone marrow failure or hypoplasia (marrow produces too few blood cells)

- Abnormal pigment patches on the tongue (dark or light patches)

- Malignancies/cancers (especially leukemia)

- Pallor (an unhealthy and pale appearance)

- Enlarged red blood cells (macrocytosis)

- Low platelet count (thrombocytopenia)

- Areas of abnormal skin pigmentation

- Frequent or unexpected nosebleeds

- Thumb abnormalities (see photos)

- Increased deep tendon reflexes

- Microcephaly (very small head)

- Heart murmur

- Easy bruising

- Short stature

- Infertility

- Anemia

Clinical features of FA

Intelligence is normal in many or most people with FA (75% of 236 patients in our literature survey were described as having normal intelligence). Many patients also have microcephaly, or a very small head (61% in our analysis). One unexpected finding in FA is that many patients have normal intelligence in spite of microcephaly. This situation is in contrast to what typically occurs in a child with poor head growth. Head growth is used as a proxy for brain growth, and poor brain growth tends to indicate poor brain development. Normal intelligence with a very small head also occurs in Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome/NBS. Distinguishing these two syndromes may be difficult (see Differential Diagnosis below), but the presence of a mutation in the gene NBN is definitive for NBS.

- Triangular-shaped face (with chin as bottom point; see photo above)

- Epicanthal folds (skin covering the inner corners of eyelids)

- Receding forehead (slopes backward)

- Receding/underdeveloped jaw

- Large or prominent ears

- Receding forehead

An important point for people of African origin is that the physical features of FA in this group are more subtle than in other groups. This fact complicates diagnosis, but lack of obvious FA facial or skeletal features should not be used to rule out a diagnosis of FA in this population (5).

As noted above, pancytopenia is common in FA (81% of patients in our literature survey). Pancytopenia is an important finding in any person because it means that something is wrong in the bone marrow. Medical problems associated with pancytopenia include pale skin, easy bleeding/poor clotting, easy bruising, fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath. All of these problems are common in FA. Blood transfusions (sometimes as often as once a week), treatment with hormones, and other therapies can help alleviate these problems. Careful monitoring of hemoglobin and other blood components is an essential part of managing FA.

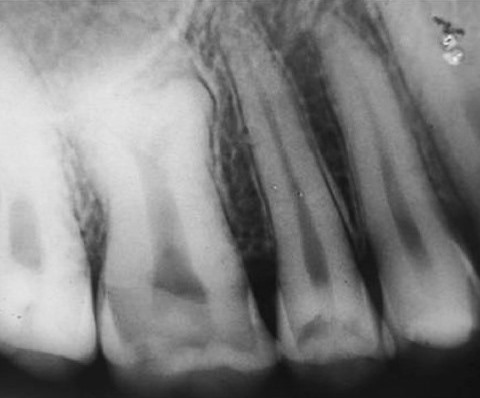

FA patients often have a variety of dental and oral problems. For example, they may experience gum disease and multiple cavities (6-9). Ulcers and gum disease can be very painful. This situation inhibits brushing, which in turn can worsen problems with the gums and cavities, and oral care in general. Other problems that have been observed in FA patients include tooth malformations (very small teeth, tooth bodies that are enlarged at the expense of the roots (7; see photo on this page), enamel problems, and extra or too few teeth). Some oral problems may appear in patients who undergo stem cell transplants (see photo on this page).

FA patients may develop tongue cancer. Squamous cell carcinomas of the tongue have been documented in a number of cases (6, 7, 10), and, as such, patients should be monitored carefully.

Cause

The vast majority of forms of FA are autosomal recessive. The term autosomal recessive means that the disorder is passed on when both parents contribute a copy of the mutated gene to their child. Many genes are assoicated with FA. They are listed below.

- FANCA (responsible for 60-70% of cases [11])

- FANCB (responsible for ~2% of cases [11])

- FANCC (responsible for ~14% of cases [11])

- FANCD2 (responsible for ~3% of cases [11])

- FANCE (responsible for ~3% of cases [11])

- FANCF (responsible for ~2% of cases [11])

- FANCG (responsible for ~10% of cases [11])

- FANCAI (responsible for ~1% of cases [11])

- BRCA2 (responsible for ~3% of cases [11])

- BRIP1 (responsible for ~2% of cases [11])

- FANCAL

- FANCAM

- MAD2L2

- PALB2

- RAD51

- RAD51C

- SLX4

- UBE2T

- XPF/ERCC4

- XRCC2

Diagnosis and Testing

FA's variety of clinical features and the large number of genes associated with it make diagnosis difficult. The following guidelines have been established to help those who suspect that a patient has FA. They have been adapted from reference 12. Again, the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund's extensive manual on FA is a highly recommended resource for guidance in diagnosing FA.

As noted above, FA is a chromosome breakage syndrome, meaning that the chromosomes are not as stable as they are in unaffected people. This phenomenon is relatively rare, and it is suggestive of a small number of disorders including FA. Special lab tests can determine if a person's chromosomes are unstable. The Fanconi Anemia Research Fund recommends that testing for chromosome breakage be the first major test performed on a person suspected of having FA. The test requires only a blood sample. White cells from the sample are cultured and treated with agents that damage chromosomes. Most people can fix this damage, but people with FA cannot. This test is recommended for people who fit the description below or who are otherwise suspected of having FA. Note that reference 13 also focuses on diagnosing FA.

Findings suggestive of FA (reference 12)

- Short stature

- Abnormal skin pigmentation (café au lait spots, extra pigment or loss of pigment)

- Skeletal malformations (thumbs, forearms)

- Microcephaly/very small head

- Eye abnormalities

- Abnormalities of the kidney, urinary tract or genitalia

- Enlarged red blood cells (macrocytosis)

- Increased fetal hemoglobin (often precedes anemia)

- Low counts of red cells, white cells, and/or platelets

- Progressive bone marrow failure

- Adult-onset aplastic anemia

- Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)

- Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML)

- Early-onset solid tumors

- Extreme adverse reactions to chemotherapy or radiation

A diagnosis can be confirmed with the chromosome testing described above and with gene sequencing that finds a mutation in one of the genes listed on this page. See the link at the right for information about labs that perform testing.

Managing FA

A variety of approaches are used to manage FA. The best source for this information is an expert clinician or the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund's manual. Blood transfusions and androgen therapy are used for increasing blood cell counts. Stem cell transplants are also used. Surgery can correct congenital malformations. In addition to many other approaches, clinical trials may provide opportunities to help test new medicines. There is a link to clinical trials in FA at the right on this page.

Differential Diagnosis

A number of other conditions are similar to FA. A sample of them are listed below. Others are described in table in the Gene Review article for NBS (see link at right).

Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS). NBS is another DNA repair/chromosome breakage disorder. FA and NBS can look very similar. Both cause microcephaly, short stature, abnormalities of skin pigmentation, and high cancer risk. People with both conditions also share certain facial features, such as a small, receding jaw. However, NBS patients do not tend to suffer from pancytopenia, and thumb malformations are rare in NBS, though they have been documented. NBS tends to occur in people of Slavic descent, and while FA should not be ruled out in a Slavic person, this ethnicity is nonetheless far more common in NBS.

Seckel syndrome (SCKS). Like FA and NBS, Seckel syndrome is another chromosome breakage disorder. Some SCKS patients develop pancytopenia. In addition, and like FA, people with SCKS may have microcephaly and short stature. Unlike FA, intellectual disability is very common in SCKS. It is typically moderate to severe, with many patients having IQs <50. Low IQ should not be used to rule out FA, as some FA patients also have intellectual disabilities. However, its presence may be more suggestive of SCKS than FA. Gene sequencing can help distinguish these conditions, as NBS, FA, and SCKS are all associated with different genes.

Other diseases that may be confused with FA include neurofibromatosis type 1 because of skin pigmentation abnormalities, TAR syndrome (thrombocytopenia with absent radii), and VACTERL association (radial ray defects). These conditions can all be distinguished from FA by the absence of chromosome breaks (12).

References

- 1. Macdougall LG et al. (1987) Fanconi anemia in black African children. Am J Med Genet 36(4):408-413. Abstract on PubMed.

- 2. Morgan NV et al. (2005) A common Fanconi anemia mutation in black populations of sub-Saharan Africa. Blood 105(9):3542-3544. Full text from publisher.

- 3. Rosendorff J et al. (1987) Fanconi anemia: another disease of unusually high prevalence in the Afrikaans population of South Africa. Am J Med Genet 27(4):793-797. Abstract on PubMed.

- 4. Rosenberg PS et al. (2011) How high are carrier frequencies of rare recessive syndromes? Contemporary estimates for Fanconi Anemia in the United States and Israel. Am J Med Genet A 155A(8):1877-1883. Full text on PubMed.

- 5. Feben C et al. (2014) Phenotypic consequences in black South African Fanconi anemia patients homozygous for a founder mutation. Genet Med 16(5):400--406. Full text from publisher.

- 6. de Araujo MR et al. (2007) Fanconi's anemia: clinical and radiographic oral manifestations. Oral Dis 13(3):291-295. Abstract on PubMed.

- 7. D'Agulham ACD et al. (2014) Fanconi Anemia: main oral manifestations. RGO, Rev Gaúch Odontol 62(3):281-288. Full text on Scielo.

- 8. Otan F et al. (2004) Recurrent aphthous ulcers in Fanconi's anaemia: a case report. Int J Paediatr Dent 14(3):214-217. Full text from publisher.

- 9. Saleh A & Stephen LX (2008) Oral manifestations of Fanconi's anaemia: a case report. S Af Dent J 63(1):28-31. Abstract on PubMed.

- 10. Alter BP (2003) Cancer in Fanconi anemia, 1927-2001. Blood 97(2):425-440. Full text from publisher.

- 11. Shimamura A & Alter BP (2010) Pathophysiology and management of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood Rev 24(3):101-122. Full text on PubMed.

- 12. Mehta PA & Tolar J (2002) Fanconia anemia. Updated 23 Feb 2017. GeneReviews [Internet] Pagon RA et al., editors. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2021. Full text.

- 13. Auerbach AD (2009) Fanconi anemia and its diagnosis. Mutat Res 668(1-2):4-10. Full text on PubMed.

- 14. McDonald R & Goldschmidt B (1960) Pancytopenia with Congenital Defects (Fanconi's Anaemia). Arch Dis Child 35(182):367-372. Full text on PubMed.

- 15. Es-Seddiki A et al. (2015) La maladie de Fanconi: á propos d'une nouvelle observation. (Fanconi anemia: report of a new case) Pan Afr Med J 20:92 doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.20.92.6116. Full text on PubMed.

- 16. Goswami M et al. (2016) Dental perspective of rare disease of Fanconi anemia: case report with review. Clin Med Insights Case Rep 9:25-30. doi: 10.4137/CCRep.S37931. Full text on PubMed.

- 17. Jayashankara C et al. (2013) Taurodontism: A dental rarity. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 17(3):478. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.125227. Full text on PubMed.