Fragile X Syndrome (FXS)

Fragile syndrome (or FXS) is a genetic condition that causes intellectual disabilities, motor problems, and a variety of physical features such as flat feet, dental problems, and heart problems. It is a member of a group of conditions called trinucleotide repeat disorders. This term refers to an abnormality in the DNA of an affected patient (see the section called Cause for more details). Other members of this group include Huntington's disease and several forms of spinocerebellar ataxia. With the exception of FXS, all of these disorders are very rare.

FXS is the most common cause of inherited mental retardation and developmental delay. It affects males more often than females, with males tending to more severely affected than females. Although the exact prevalence of FXS is unknown, estimates exist. In males, it ranges from a low of 1 person in 4,000 to a high of 1 in 1,250, while in females, it ranges from 1 person in 9,000 to 1 in 2,500 (1, 2; reviewed in 3, 4). Some people believe that FXS may be even more common, as very mild cases may not be diagnosed.

Clinical information

The clinical features of FXS are somewhat variable, although a small number of features can help identify it. Unfortunately, the most common features of FXS are also common in many other disorders. This overlap complicates diagnosis. In addition, some of the standout features of FXS may not appear until a patient reaches puberty. The most common features are listed below.

- Intellectual disability

- Delayed speech development

- Delayed motor development

Very common features of fragile X syndrome

Intellectual disability tends to be in the moderate range in boys and in the mild range in girls. Boys with a full methylation defect (see Cause, below) have the lowest IQ, with an average of roughly 40 (5). Roughly half of girls with the fragile X mutation are clinically normal (6), with the rest split between an IQ <70 or in the borderline range (7-9). Girls with normal IQs may have learning disabilities (10), including relative weaknesses with mathematics (10-12) and certain areas of memory (13).

Other common clinical features of FXS are listed below.

- Tactile defensiveness/negative response to touch

- Stereotypy (repetitive movements or utterances)

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder/ADHD

- Aggressive behavior (more common in boys)

- Mouthing of objects past the typical age

- Gaze avoidance or poor eye contact

- Hand flapping or waving movements

- Autism or autism spectrum

- Large testicles (may not occur until puberty)

- Large or prominent ears

- Highly arched palate

- Long, narrow face

- Large forehead

- Flat feet

- Vertical crease on feet or between large/second toes

- Cardiac abnormalities

- Sunken chest

- Seizures

Common clinical features of fragile X syndrome

Autism and autism-like behaviors are common in fragile X syndrome, and are useful for diagnosis (see section called Diagnosis, below).

Cardiac abnormalities occur in a minority of patients and are more common in adults. The most common problems appear to be heart murmur, aortic dilatation, and mitral valve prolapse (14-17).

In addition, it has been found that many people with FXS cannot touch their tongues to their lips (18). This trait may be a useful aide when considering FXS as a possible diagnosis.

Many people with FXS have a distinctive facial appearance. The most easily identified characteristics are large and/or prominent ears, and a long narrow face. They may also have a large forehead and strabismus (eyes that are not aligned). It is important to note that a minority of people with FXS do not have these facial features, and that they may only become apparent during puberty. Facial features characteristic of FXS are evident in the young boy pictured at the top right of this page.

Cause

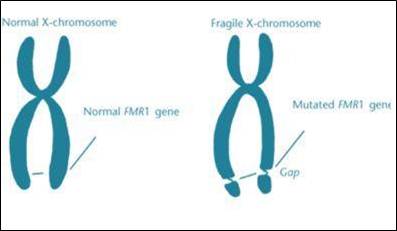

Fragile X syndrome is caused by a mutation on the gene FMR-1 (19, 20). FMR-1 is located on the X chromosome, meaning that FXS syndrome is an X-linked disorder. Females have two X chromosomes, and males have one. This is why mutations and other abnormalities on the X chromosome tend to affect males more seriously than females --- if a female inherits a faulty copy of the chromosome, she will likely have a normal copy that can compensate for the faulty one.

A mutated gene on an X chromosome can be passed from fathers to daughters or from mothers to sons or daughters. Fathers pass Y chromosomes to their sons and therefore cannot transmit a damaged X chromosome to a boy.

The mutation that occurs in FMR-1 is called a trinucleotide repeat expansion. This term means that a sequence of 3 DNA base pairs (a trinucleotide) is repeated over and over again. In FXS, the sequence is CGG. In general with disorders in the trinucleotide repeat group, the more times the sequence is repeated, the more severe the disease.

In the healthy population, the CGG sequence is repeated 5-50 times, with an average of 30 (6). People with 55-200 CGG repeats have what is called a premutation. Many people in this group have no clinical features of fragile X syndrome, although some may have mild to very mild clinical features (reviewed in 22). Physical features may include prominent ears and lax joints. The question of the effects of a premutation on behavior and cognitive ability have not been completely answered. However, some studies have found that patients may have mild emotional impairments, mild deficiencies with memory and attention span, and problems with executive function. People with premutations may also have higher rates of hostility, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms compared to people without the premutation (all information reviewed in 22). Premutations can be passed to offspring. Some become unstable and may expand in future generations (23).

Roughly 20% of females with premutations have primary ovarian insufficiency, and 30% of males over age 50 develop a disorder called fragile x-associated tremor and ataxia syndrome (FXTAS). In addition to tremors and ataxia, people with FXTAs also develop as cognitive and psychiatric problems (reviewed in 24).

Finally, people with >200 repeats are said to have full mutations, which result in fragile X syndrome.

Diagnosis and Testing

The American College of Medical Genetics has established guidelines for when testing for FXS should be considered (25). They are as follows:

- A person with mental retardation, developmental delay, or autism, especially if the person has any behaviors that occur in FXS, or any family members/relatives with mental retardation or fragile X syndrome.

- People in reproductive counseling who have either a family history of fragile X syndrome or undiagnosed mental retardation.

- Fetuses of mothers who are carriers.

- Affected individuals who have had a positive cytogenetic test and are seeking counseling related to the risk that they or their relatives are carriers. This test was not as accurate as the current DNA test, and DNA testing is advised in order to distinguish premutation carriers from women with the full mutation.

Differential Diagnosis

As noted above, FXS is a relatively common condition in terms of rare diseases. Diagnosis can be difficult because presentation is variable and because some clinical features do not always become apparent until puberty. A number of other conditions resemble FXS, and are described below.

Fragile XE syndrome (also called FRAXE and fragile XE mental retardation). People with this condition have mild intellectual disabilities, including mild mental retardation and learning disabilities. Male patients tend to have IQs in the borderline range (70s to as high as 80-85, depending on which definition is used), and females are rarely diagnosed because symptoms are so mild. Clinical features include speech delays, short attention span, hyperactive behavior, and poor writing skills. Some patients may also have autistic behaviors seen in FXS, including hand flapping and repetitive behaviors. FRAXE is very rare and affects 1 person in 25,000 to 1 person in 100,000 (26). Distinguishing the two conditions may require DNA testing.

Renpenning syndrome (RS) is another X-linked disorder that causes mental retardation. Like FXS, it causes moderate mental retardation. It may also cause mild short stature, which may be seen in FXS. Unlike FXS, however, people with RS tend to have small testes (noticeable around the time of puberty) and small heads/microcephaly. In contrast, FXS patients generally have large testes by the time of puberty, and they also have large heads (macrocephaly) for their age or body size. Some FXS patients who do not have macrocephaly may still have a head size that is greater than the 50th percentile for age. RS is also an X-linked disorder, and is caused by mutations in the gene PQBP1. Prevalence is not known, and <100 cases have been reported in the literature.

Prader Willi syndrome. Like FXS, PWS causes intellectual disabilities, delays in speech & motor development, and behavior problems. Although most cases of PWS are dissimilar to FXS, there is a form of FXS called the Prader-Willi phenotype. The clinical features of fragile X syndrome are present in these patients. In addition, like PWS patients, members of this group have hypotonia/floppiness as infants and develop overeating and obesity problems. DNA testing for mutations in FMR1 and for imprinting defects on chromosome 15 can distinguish the two conditions. In addition, patients with the FXS-PWS phenotype may have close family members or relatives with classical FXS clinical features.

Other conditions in the differential diagnosis of fragile X syndrome may be found in reference 27.

References

- 1. Turner G et al. (1996) Prevalence of fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet 64(1):196-197. Abstract on PubMed.

- 2. Webb TP et al. (1986) The frequency of the fragile X chromosome among schoolchildren in Coventry. J Med Genet 23(5):396-399. Full text on PubMed.

- 3. Crawford DC et al. (2001) FMR1 and the Fragile X Syndrome: Human Genome Epidemiology Review Genet Med 39(5):359-371. Full text on PubMed.

- 4. Koukoui SD & Chaudhuri A (2007) Neuroanatomical, molecular genetic, and behavioral correlates of fragile X syndrome. Brain Res Rev 53(1):27-38. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 5. Merenstein SA et al. (1996) Molecular-clinical correlations in males with an expanded FMR1 mutation. Am J Med Genet 64(2):388-394. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 6. Zitelli BJ & Davis HW (2007) Atlas of Pediatric Physical diagnosis (5th edition). Philadelphia, Mosby Elsevier pp. 15-17. Book on amazon.com

- 7. Sherman SL et al. (1985) Further segregation analysis of the fragile X syndrome with special reference to transmitting males. Hum Genet 69(4):289-299. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 8. Hagerman RJ et al. (1992) Girls with fragile X syndrome: physical and neurocognitive status and outcome. Pediatrics 89(3):395-400. Abstract on PubMed.

- 9. Loesch DZ & Hay DA (1988) Clinical features and reproductive patterns in fragile X female heterozygotes. J Med Genet 25(6):407-414. Full text on PubMed.

- 10. Miezejeski CM et al. (1986) A profile of cognitive deficit in females from fragile X families. Neuropsychologia 24(3):405-409. Abstract on PubMed.

- 11. Kemper MB et al. (1986) Cognitive profiles and the spectrum of clinical manifestations in heterozygous fra (X) females. Am J Med Genet 23(1-2):139-156. Abstract on PubMed.

- 12. Brainard SS et al. (1991) Cognitive profiles of the carrier fragile X woman. Am J Med Genet 38(2-3):505-508. Abstract on PubMed.

- 13. Freund LS et al. (1991) Cognitive profiles associated with the fra(X) syndrome in males and females. Am J Med Genet 38(4):542-547. Abstract on PubMed.

- 14. Crabbe LS et al. (1993) Cardiovascular abnormalities in children With fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics 191(4):714-715. Abstract on PubMed.

- 15. Loehr JP et al. (1986) Aortic root dilatation and mitral valve prolapse in the fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet 23(1-2):189-194. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 16. Sreeram N et al. (1989) Cardiac abnormalities in the fragile X syndrome. Br Heart J 61(3):289-291. Full text on PubMed.

- 17. Hagerman RJ & Synhorst DP (1984) Mitral valve prolapse and aortic dilatation in the fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet 17(1):123-131. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 18. Lachiewicz AM et al. (2000) Physical characteristics of young boys with fragile X syndrome: reasons for difficulties in making a diagnosis in young males. Am J Med Genet 92(4):229-236. Absract on PubMed. Full text.

- 19. Verkerk A et al. (1991) Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster regionexhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell 65(5):905-914. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 20. Oberlé I et al. (1991) Instability of a 550-base pair DNA segment and abnormal methylation in fragile X syndrome. Science 252(5009):1097-1102. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 22. Van Esch H (2006) The Fragile X premutation: new insights and clinical consequences. Eur J Med Genet 49(1):1-8. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 23. Fu YH et al. (1991) Variation of the CGG repeat at the fragile X site results in genetic instability: resolution of the Sherman paradox. Cell 67(6):1047-1058. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 24. Hagerman P (2013) Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS): pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol 126(1):1-19. Full text on PubMed.

- 25. Sherman S et al. (2005) Fragile X syndrome: Diagnostic and carrier testing Genet Med 7(8):584-587. Full text on PubMed.

- 26. Youings SA et al. (2000) FRAXA and FRAXE: the results of a five year survey. J Med Genet 37(6):415-421. Full text on PubMed.

- 27. Saul RA & Tarleton JC (1998) FMR1-related disorders. Updated April 26, 2012. GeneReviews [Internet] Pagon RA et al., editors. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2021. Full text.

- 28. Saxon P (2014) Boy with Fragile X syndrome smiling. Photo found on Wikimedia Commons.

- 29. Saxon P (2014) Boy with Fragile X syndrome playing with toy. Photo found on Wikimedia Commons.

- 30. Garber KB et al. (2008) Fragile X syndrome. Eur J Hum Gen 16(6):666-672. Full text on PubMed.

- 31. Image from the Ransom Notes wiki.