Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS)

Prader-Willi Syndrome, often called PWS, is one of two sister conditions caused by abnormalities on chromosome 15. The other one is Angelmen syndrome. In spite of having the same origin, PWS and Angelman syndrome are very different disorders. This is because of how the syndrome is transmitted. In PWS, patients receive a defective piece of chromosome 15 from their fathers, whereas in Angelman syndrome, they receive a defective piece of chromosome 15 from their mothers. The same part of the chromosome is defective in both cases, but, because of a phenomenon called imprinting, different genes are turned on and off on the maternal and paternal chromosomes. This fact is what causes the different syndromes. For more information, see the section below, entitled Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes.

Clinical information

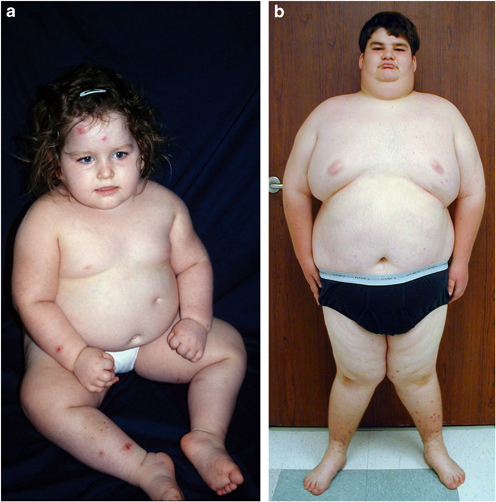

In very young patients, PWS is characterized by hypotonia (see photograph at the top right). Infants with hypotonia are floppy and have poor muscle control. They may also be lethargic. The problem can affect a developing fetus, and can be observed as the fetus not moving as much as expected. In addition, the baby may also be born in the breech position, which is thought to be due to hypotonia interfering with the baby's movements. Note: not all breech births are due to hypotonia. After birth, infants with PWS generally have feeding problems caused by to a poor ability to suck milk. This fact leads to poor weight gain, and tube feeding is necessary in some patients. Again, this problem is caused by poor muscle control due to hypotonia. Many infants also have a weak cry and do not develop motor skills when expected (head control, sitting independently, and walking are examples).

Hypotonia typically improves in PWS patients, although adults with PWS are generally still mildly affected. As the hypotonia becomes less problematic, eating and weight gain improve. This status is actually a phase of PWS, and it usually lasts from late infancy until roughly age 2. During this period, growth and appetite are in the normal range. When it ends, most children begin to gain weight without consuming extra calories. This is because their metabolic rates are slow (many PWS patients need only 60% of the calories expected for their ages and size; 1). Children next enter a phase in which they develop insatiable appetites. This problem appears to be caused by an abnormality in the hypothalamus, a part of the brain that controls appetite. It causes PWS patients to always feel hungry, even if they have just eaten a large meal. If allowed, they will eat continuously, hoard food, or even eat pet food or garbage. Thus, it is very important that caregivers ensure that people with do not have free access to food. Treatment with growth hormones may have a beneficial effect on weight gain (2).

The timing of nutritional phases in PWS varies. A recent study that described them in detail found that the period of feeding difficulties usually stops between the ages of 5 and 15 months with a median ending age of 9 months (3). The phase of healthy weight gain appears to end by 31 months in most patients (median age: 25 months). After this point, weight increases substantially with no change in food intake. During this period, appetite is normal and children may still feel full. Next, typically around ages 4.5 to 8, appetite increases, patients stop experiencing a feeling of being full, and weight gain increases. At this point, patients may complain of always feeling hungry. A small number of adults may reach a final phase where they begin to feel full again. This transition appears to occur only in a minority of patients.

The common features of PWS are as follows.

- Hypotonia in infancy

- Feeding difficulties in infancy

- A weak cry in infancy

- Lack of energy/lethargy in infancy

- Intellectual disability

- Delayed speech and motor development

- Small genitals

- Undescended testicles in boys

- Narrow forehead

- Almond-shaped eyes

- Strabismus (eyes not aligned; e.g. cross-eyed)

- Downward-turning corners of the mouth

- Small hands and feet

- Temper tantrums, especially when food is denied

- Skin-picking

- Low sensitivity to pain

- Thick, sticky/gooey saliva

Children with PWS have abnormalities of growth hormone secretion (4). This problems makes them shorter than other children their age. They also do not experience a growth spurt in adolescence. Growth hormone insufficiency also changes body composition from normal, causing a relative increase in body fat and a relative decrease in muscle.

Growth hormone therapy is FDA-approved for treating PWS, and can help with a number of problems. The most dramatic changes occur in the first year of treatment. They include increased growth rate (height, hands, and feet), with a decrease in body mass index (BMI). Muscle development also improves, as does resting energy expenditure (the number of calories burned while at rest). Other benefits include better respiratory function and improvements in cholesterol levels, and increased head growth. IQ, behavior, and appetite do not change.

Treatment may begin as early as early infancy (2-3 months of age), and must begin before puberty. Generally, the earlier treatment begins, the more effective it will be. However, treatment also appears to be beneficial for adults (5, 6), as it can increase lean mass and decrease fat mass.

A thorough medical evaluation is important prior to beginning growth hormone therapy. Caregivers must also be aware of adverse effects of this treatment, which include relatively minor ones such headaches and swelling, as well as more serious ones, such as increased insulin levels and respiratory dysfunction. A large patient support group, Prader-Willi Syndrome USA, has written a detailed publication for families about growth hormone therapy in PWS. Publications for clincians include references 7 and 8.

Diagnosis and Testing

Prader-Willi syndrome can generally be diagnosed by the presence of a combination of clinical features outlined below. However, confirming the diagnosis with lab testing is also very important. The clinical criteria for diagnosis were outlined in 1993, and remain accurate (9).

- Birth up to age 2: Hypotonia with poor suck/feeding problems.

- Ages 2 to 6: Global developmental delay with hypotonia and a history of feeding problems.

- Ages 6 to 12: Excessive appetite/eating, obesity if food intake not controlled, and a history of the previously noted problems. Hypotonia may persist.

- Ages 13 to adulthood: Intellectual disability, excessive eating with obesity if uncontrolled, hypothalamic hypogonadism (small genitals due to underproduction of sex hormones), and/or typical behavior problems. (e.g. temper tantrums, manipulative behavior, obsessive-compulsiveness, and/or skin picking).

A person who meets all the conditions for a given age should be tested for PWS (see link to testing facilities at right).

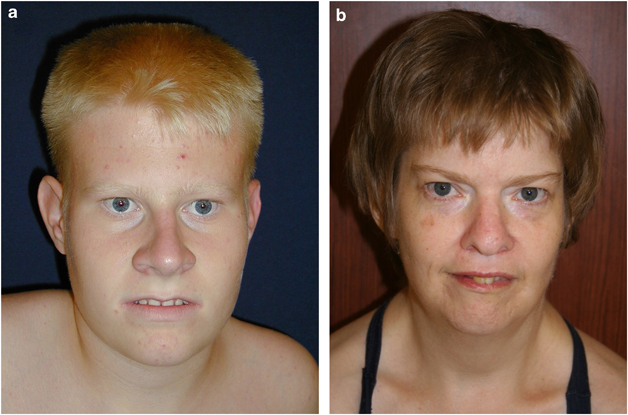

Angelman syndrome and PWS

PWS and Angelman syndrome (AS) are often called sister syndromes because they are caused by abnormalities in the same sections of chromosome 15. However, in spite of their similar origins, the two disorders are very different. For example, children with AS do not eat excessively and are typically non-verbal or have a very limited vocabulary. AS patients are also prone to outbursts of laughter for no apparent reason, and have gait and other ataxias. PWS do have some similarities, such as hypotonia, global developmental delay, and skin/hair/eyes that are paler than expected. Generally, however, distinguishing the two syndromes is not difficult.

PWS occurs when there are abnormalities on a stretch of chromosome 15 that is contributed by a person's father. AS occurs when the same stretch of abnormal chromosome is contributed by the person's mother. Different genes are turned on and off in the maternal and paternal chromosomes, a phenomenon called imprinting. When the child inherits a defective copy of chromosome 15 from his father, the maternal chromosome cannot compensate, because the PWS genes are turned off. The reverse is true in AS: the maternal chromosome is abnormal, and paternal copy cannot compensate.

In most cases of PWS and AS, part of chromosome 15 is deleted. In a minority of cases, a child receives two copies of chromosome 15 from one parent. If both come from the father, PWS results; if they come from the mother, AS results. Alternatively, AS occurs if there are mutations in the gene UBE3A. The specific genes involved in PWS are not yet known. Most cases of PWS and AS are sporadic, which means that the chromosome 15 abnormalities were not present in the parent and occured for no known reason. There is nothing that either parent could have done to prevent the problem. In these cases, the chance that parents will have another affected child is less than 1%. In rare cases, one parent carries a mutation and passes the mutation to the child. Genetic counseling can address questions of inheritance and risk to future siblings.

Differential Diagnosis

Several conditions share clinical features with PWS, but only one has a close resemblance after infancy. In infancy, a number of conditions present with hypotonia. Physical exams and lab investigations can help distinguish different causes of this problem; for an overview, see reference 10. Infants with PWS are likely to be globally delayed, meaning that they do not meet motor, social, and cognitive milestones.

Hyperphagic short stature (HSS; also called psychosocial short stature) is characterized by short stature or growth failure. This disorder generally occurs in children who live in a psychologically damaging environment and who suffer from emotional deprivation. Signs of HSS that mimic PWS include failure to thrive in infancy, excessive eating, food hoarding, short stature, and behavior problems. Patients may also have developmental delays, be depressed, have sleep disturbances, and be relatively insensitive to pain. Fasting levels of growth hormone may be low, but the cause appears to be environmental. However, there may be a genetic predisposition to this condition (11). PSS appears to occur mainly in Caucasians (12). Removing a child from the stressful environment is the most important part of treating PSS. Growth hormone deficiency is very responsive to this treatment (Gilmour).

Fragile X syndrome. Fragile X syndrome is a disorder characterized by intellectual disability (generally moderate in males and mild in females), as well as a long face with a prominent forehead (also seen in PWS). Other clinical features that are shared with PWS include behavior problems and floppiness/hypotonia in infants. However, infants with fragile X syndrome generally do no have the sucking/feeding sucking problems that are nearly universal in PWS, nor do they have hypogonadism or the appetite problems associated with PWS.

References

- 1. Butler MG et al. (2011) Prader-Willi Syndrome: Obesity due to Genomic Imprinting. Curr Genomics 12(3):204-215 Full text on PubMed.

- 2. Cassidy et al. (2012) Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 155A(5):1040-1049. Full text from publisher.

- 3. Miller JL et al. (2011) Nutritional phases in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Med Genet 37(1):1-8. Full text on PubMed.

- 4. Burman P (2001) Endocrine dysfunction in Prader-Willi syndrome: a review with special reference to GH. Endocrin Rev 22(6):787-799. Full text from publisher.

- 5. Butler MG et al. (2013) Effects of Growth Hormone Treatment in Adults with Prader-Willi Syndrome. Growth Horm IGF Res 23(3):81-87. Full text on PubMed.

- 6. Mogul HR et al. (2008) Growth hormone treatment of adults with Prader-Willi syndrome and growth hormone deficiency improves lean body mass, fractional body fat, and serum triiodothyronine without glucose impairment: results from the United States multicenter trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93(4):1238-2145. Full text from publisher.

- 7. Emerick JE & Vogt KS (2013) Endocrine manifestations and management of Prader-Willi syndrome. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2013(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1687-9856-2013-14. Full text on PubMed.

- 8. Aycan Z & Baş VN (2014) Prader-Willi syndrome and growth hormone deficiency. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 6(2):62-67 Full text on PubMed.

- 9. Holm VA et al. (1993) Prader-Willi syndrome: consensus diagnostic criteria. Pediatrics 91:398-402. Abstract on Pubmed.

- 10. Leyenaar J et al. (2005) A schematic approach to hypotonia in infancy. Paediatr Child Health 10(7):397-400. Full text on PubMed.

- 11. Gilmour M (2001) Hyperphagic short stature and Prader-Willi syndrome: a comparison of behavioural phenotypes, genotypes and indices of stress. Br J Psychiatr 179:129-137. Full text from publisher.

- 12. Source: Medscape.

- 13. Weiss HR & Goodall D (2009) Scoliosis in patients with Prader Willi Syndrome - comparisons of conservative and surgical treatment. Scoliosis 4:10. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-4-10. Full text on PubMed.

- 14. Cassidy SB & Driscoll DJ (2008) Prader-Willi syndrome Eur J Hum Genet 17(1):3-13 Full text on PubMed.