Susac's Syndrome (SS)

Susac's Syndrome, sometimes Susac Syndrome (SS) is also known as retinocochleocerebral vasculopathy, microangiopathy with retinopathy, encephalopathy and deafness (RED-M), or small infactions of cochlear, retinal and encephalic tissues (SICRET) syndrome. SS is a neurological disease affecting the endothelium (lining) of small blood vessels in the brain, inner ear, and retina.

SS is extremely rare, having been reported in only ~300 patients since its initial description in the late 1970s (1). Due to underdiagnosis, the incidence of this disease is likely much higher than previously estimated, however. SS may initially present without the full array of symptoms, or with symptoms which are easily misinterpreted (see differential diagnoses below).

SS seems to occur in all ethnicities, though most cases occur in the Northern Hemisphere. Patients tend to be female (3:1) and onset is usually between the ages of 20 and 40 years, although cases have been reported as young as age 3 and as old as 70. SS is currently believed to be of autoimmune origin, though risk factors for it are unknown at this time (2-6).

Clinical information

Susac's Syndrome consists of a triad of encephalopathy, branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO), and hearing loss. Most patients do not present with all three elements of this triad at onset. Patients with SS usually have difficulties with cognition and other brain functions, and may also present with losses of vision and/or hearing. Initial impairments of hearing or vision may not be seen as significant by patients with CNS involvement, and may go unreported to clinicians (2, 4). Differences in underlying involvement (brain, retina, inner ear) also result in differing clusters of symptoms (2, 3, 6). This can make diagnosis difficult. SS patients commonly have some combination of the following problems:

- Persistent, severe headache (may mimic migraine with or without aura)

- "Holes" in otherwise normal field of vision (scotoma, caused by BRAO)-- may be transient and/or sudden

- Hearing loss, vertigo and/or tinnitus

- Psychiatric disturbances or personality changes

- Confusion, memory difficulties or cognitive decline

- Dementia

- Loss of motor function-- ataxia, slurring of speech, or clumsiness

- Seizures

- Myoclonus

Common problems in SS

The etiology of SS is currently poorly understood. It is believed to have autoimmune origins. Like other autoimmune disorders, SS is more common in females than in males, and responds best to immunosuppressive therapies. It seems to be more commonly diagnosed in persons residing in the Northern Hemisphere. No lifestyle or genetic risk factors have been identified (2, 3).

SS seems to be self-limiting and often stabilizes within 2 to 4 years. Remission can result in complete resolution of symptoms and full recovery. More rarely, chronic and recurring cases have been reported. Most patients experience one acute episode that lasts a year or more, but do not experience recurrence (2, 3, 6).

Encephalopathy can be severe, and may result in permanent disability in those patients who develop severe CNS disturbances such as dementia or loss of motor function. To prevent this outcome, SS with encephalopathy is usually treated aggressively with immunosuppressants upon diagnosis. For the most optimal outcomes, it is important to obtain a correct diagnosis early in the course of the episode. Hearing loss is often permanent after the resolution of the acute episode; mitigating measures such as hearing aids or cochlear implants have been used with success in some patients (7). There is a subset of patients with recurrent BRAO as the dominant feature, and these patients may benefit from differentiated treatment (see below). Vision changes can usually be expected to resolve upon remission of symptoms.

Susac's syndrome has three general clinical courses:

- Monocyclic disease, characterized by some fluctuations, but eventually remitting after a course of 1-2 years

- Polycyclic disease with remission between episodes that lasts more than 2 years

- Chronic continuous disease without remission for more than 2 years

Lifelong monitoring of SS patients is recommended due to the risk of relapse, which may occur decades after the resolution of acute symptoms (1, 2).

Diagnosis and Testing

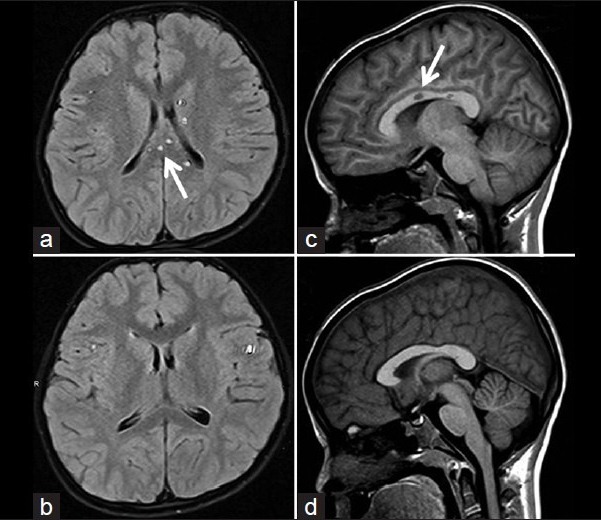

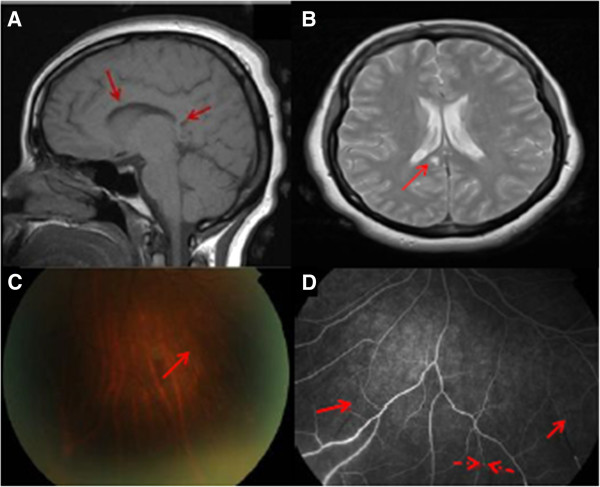

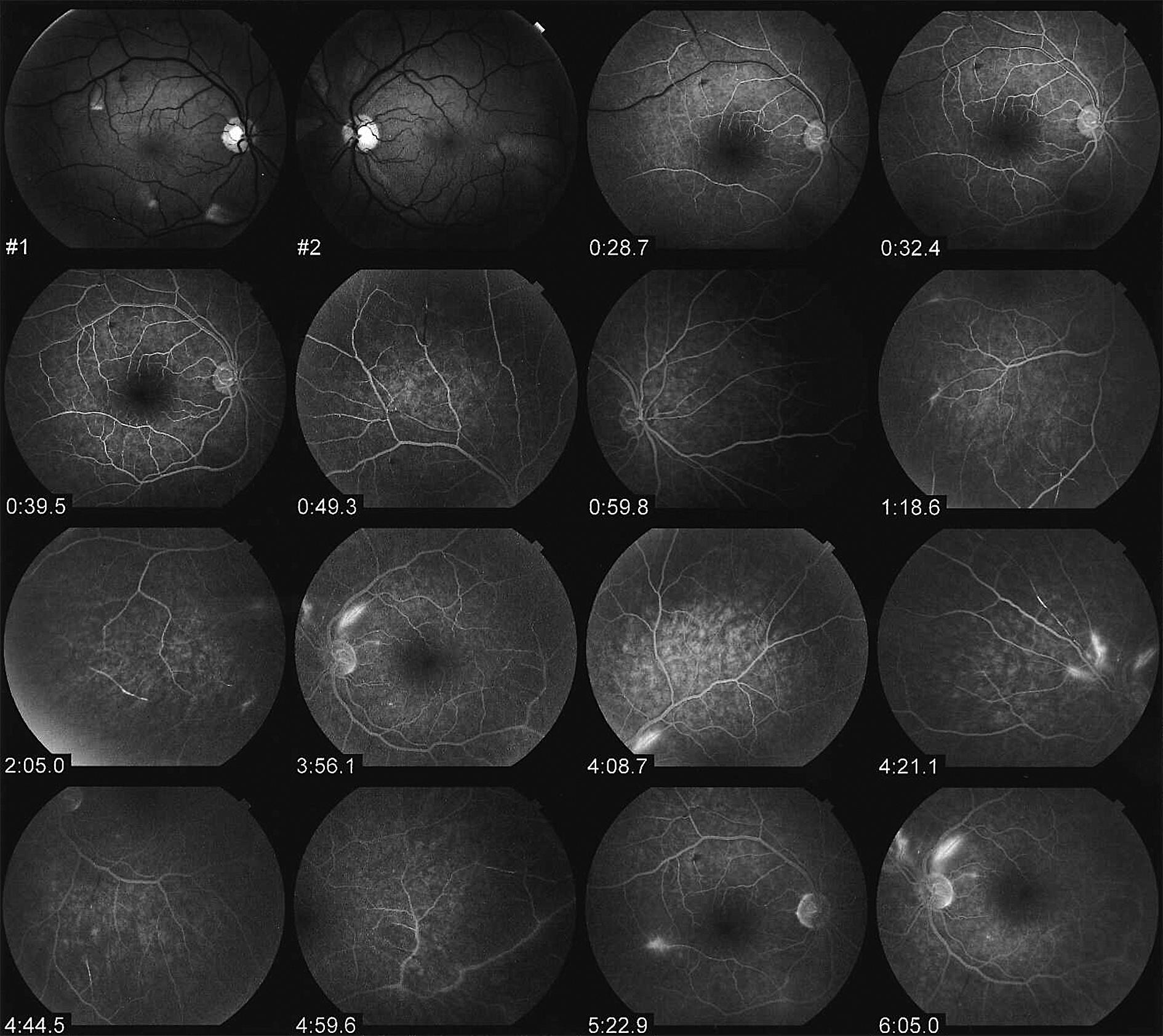

For proper diagnosis, it is important to obtain enhanced MRI images that clearly show lesions and inflammatory processes within the corpus callosum. These images should show regions of hypointensity in the central corpus callosum ("hole-punch", "spoke" or "spike" lesions). MRI-FLAIR T2 may also show regions of hyperintensity ("snowball" or "string of pearls" lesions) in the periventricular region. Please see the photos at the top right of this page (a larger image is available) and below for examples. A combination of central callosal lesions and string of pearls lesions is said to be pathognomonic for Susac's syndrome (8). In addition, the results of fluorescein angiography can also be highly indicative of the disease; in particular, arteriolar wall hyper-fluorescence is a strong indicator of SS, with or without BRAO (2).

Patients may not initially present with the triad noted above, and may develop additional problems over the course of the disease's duration. As a result, continuous monitoring may be advised in any person suspected of having SS or diagnosed with it. It is also important to obtain imaging of the retina and audiograms to establish the degree of involvement in these other systems. In addition, recent literature suggests that BRAO may occur in patients who are apparently asymptomatic, and it remains an important diagnostic feature (2, 3).

- Lesions of the central corpus callosum (see photos at right and below) visible on sagittal MRI

- Sensorineural hearing loss upon audiography, often of low and/or mid-range frequencies-- may be sudden in onset

- Elevated protein in CSF

- Gass plaques or "cotton-wool" spots upon examination of the retina

- Fluorescein leakage upon retinal fluorescein angiography (see angiogram series below)

- Arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence (may be at sites distant from occlusions)

- Retinal examination shows BRAO (see photos)

- Bilateral extensor plantar responses (Babinski's sign)

Differential Diagnosis

Susac's syndrome that presents as encephalopathy may be misdiagnosed as complex migraine. It may also be mistaken for an inflammatory demyelinating CNS disease such as multiple sclerosis (MS), acute disseminated encephalitis (ADEM), or neuromyelitis optica (Devic's disease). Other possible diagnoses involving the triad of affected systems include Meniere's disease, malignancy, infection, or autoimmune disorders such as antiphospholipid syndrome, autoimmune inner-ear disease, Behçet disease, Churg-Strauss syndrome, Cogan syndrome, Eales disease, limbic encephalitis, polyarteritis nodosa, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and Wegener granulomatosis (2-5).

SS does not respond to migraine control medications. While it often responds well to corticosteroids (like other autoimmune disorders), symptoms will generally return upon tapering of steroid doses during the first months or year(s) of such treatment (2-4).

MS may cause brain lesions that look similar to those seen on MRIs of Ss patients. However, distinctive lesions (described variously in literature as "snowball," "spoke," or "hole-punch" lesions) that are concentrated exclusively in the central corpus callosum are considered to be hallmarks of SS. MS lesions tend to be more widely distributed, seldom appearing exclusively in the central corpus callosum. In both MS and ADEM, the undersurface and septal interface of corpus callosum are involved (6).

SS generally causes an elevation of protein in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and occasionally pleocytosis. In addition, SS encephalitis is very frequently associated with BRAO and/or hearing loss upon careful examination. Even patients who seem asymptomatic for BRAO and hearing loss should be evaluated when presenting with encephalitis (2, 4).

It is helpful to recognize the specific clinical observations which may be associated with the triad of affected systems in SS, but it is also important to recognize that not all patients will present initially with all of the clinical signs.

Treatment

There is currently a lack of evidence-based treatment for SS (2, 3, 6). As a result, treatments have been developed empirically with individual patients. Generally, encephalitis patients appear to respond well to steroid immunosuppression. Other treatments include intravenous immunoglobin (IVIG), aspirin therapy, plasma exchange (PLEX), and/or more aggressive immunosuppression with azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, infliximab and/or rituximab (2, 6).

Because arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence is a useful proxy for endothelial involvement in the course of SS, serial fluorescein angiography can be used as a monitoring tool for assessment of response to immunosuppressive therapy (2, 4). As noted above, involvement of the retina or cochlea may be asymptomatic or nearly asymptomatic in some patients, in spite of clear evidence of impairment in angiograms and audiograms (4).

References

- 1. Susac JO et al. (1979) Microangiopathy of the brain and retina. Neurology 29(3):313-316. Abstract on PubMed.

- 2. Nazari F et al. (2014) What is Susac syndrome? - A brief review of articles. Iran J of Neurol 13(4):209-214. Full text on PubMed.

- 3. Freua F et al. (2014) Susac syndrome. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr 72(10):812-813. Full text from Scielo.

- 4. Boukouvala S et al. (2014) Detection of branch retinal artery occlusions in Susac's syndrome. BMC Res Notes 7:56. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-56 Full text on PubMed.

- 5. Prakash G et al. (2013) Susac's syndrome: First from India and youngest in the world. Ind J Ophth 61(12):772-773. Full text on PubMed.

- 6. Mateen FJ et al. (2012) Susac syndrome: clinical characteristics and treatment in 29 new cases. Eur J Neurol 19(6):800-811. Abstract on PubMed.

- 7. Roeser MM et al. (2012) Susac syndrome--a report of cochlear implantation and review of otologic manifestations in twenty-three patients. Otol Neurotol 30(1):34-40. Abstract on PubMed.

- 8. Rennebohm R et al. (2012) Susac's Syndrome--update. J Neurol Sci 299(1-2):86-91. Abstract on PubMed.