Williams syndrome (WS)

Clinical information

Williams syndrome is a genetic condition. People with WS tend to have cardiovascular problems, learning and other cognitive disabilities, and developmental delays. Cardiovascular problems can be serious and/or life threatening. In addition, people with WS tend to be friendly and sensitive. The prevalence of WS was stated as roughly 1 person in 20,000 for many years, but a 2003 study in Norway found a prevalence there of 1 in 7,500 people (1). Williams syndrome shares many similarities with Costello syndrome.

One standout trait in people with Williams syndrome is a stellate iris (starburst-like pattern in the iris; see photo below). This pattern is most obvious in patients with pale eyes (blue, green, hazel, and light brown), but careful investigation with slit lamp microscopy may reveal it in patients with dark brown eyes (2). Note that blue eyes are common in patients with this syndrome, making the pattern easy to see. Although this pattern does not occur in all WS patients, its presence, in combination with other features of the syndrome, is highly suggestive of WS.

The following are other common features of WS:

- High sensitivity to sound

- Lax/loose joints (young children)

- Stiff joints (older children/adults)

- Hearing loss

- Intellectual disability

- Short stature

- Prematurely grey hair

- Loose and/or soft skin

- Small teeth

- Maloccluded/crooked teeth

- Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- Gait ataxia

- Inguinal or umbilical hernias

- Abnormal curvature of the spine

Medical problems in WS

A small number of infants and young children with Williams syndrome may have hypercalcemia (elevated blood calcium). Although the problem often resolves itself as a child grows (often by the second birthday), treatment may be needed (3). Hypercalcemia is not a necessary componente of the diagnosis of WS.

People with WS may also not properly metabolize calcium and vitamin D. In addition, people with WS may have problems with progressive joint limitation. This means that joints become tighter and less mobile as children age. In spite of this fact, infants and very young children with Williams syndrome may be hypotonic (floppy or limp), and their joints may be lax/loose. As they age, muscle tone increases: their heel cords and hamstrings get gradually tighter. Toe walking is common in children who are old enough to attend school. Physical therapy can help with these problems.

Patients with Williams syndrome tend to have a distinctive facial appearance. This trait can make them relatively easy to recognize. Specific facial features include the following:

- Large forehead

- Large or thick lips

- Large or full cheeks

- Wide smille

- Long philtrum (groove below the nose)

- Flat nasal bridge

- Widely spaced teeth

- Small chin

- Epicanthal folds

- Eyes that may appear to be "puffy"

- Stellate iris (in ~70% of patients)

Facial features in WS

In addition, cardiac problems are very common in the WS population, and they may have the following problems (this list is not exhaustive):

- Supravalvar aortic stenosis (SVAS)

- Peripheral pulmonary stenosis (PPS)

- Supravalvar pulmonary stenosis (SVPS)

- Pulmonary artery stenosis (PAS)

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Mitral valve regurgitation or other insufficiency

- Pulmonary valve stenosis (PS)

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Ventricular septal defect (VSD)

- Atrial septal defect (VSD)

- Heart murmur

- Valvar aortic stenosis (AS)

Common cardiac problems in WS

There is extensive literature on cardiac problems in Williams syndrome (3-7; list not exhaustive).

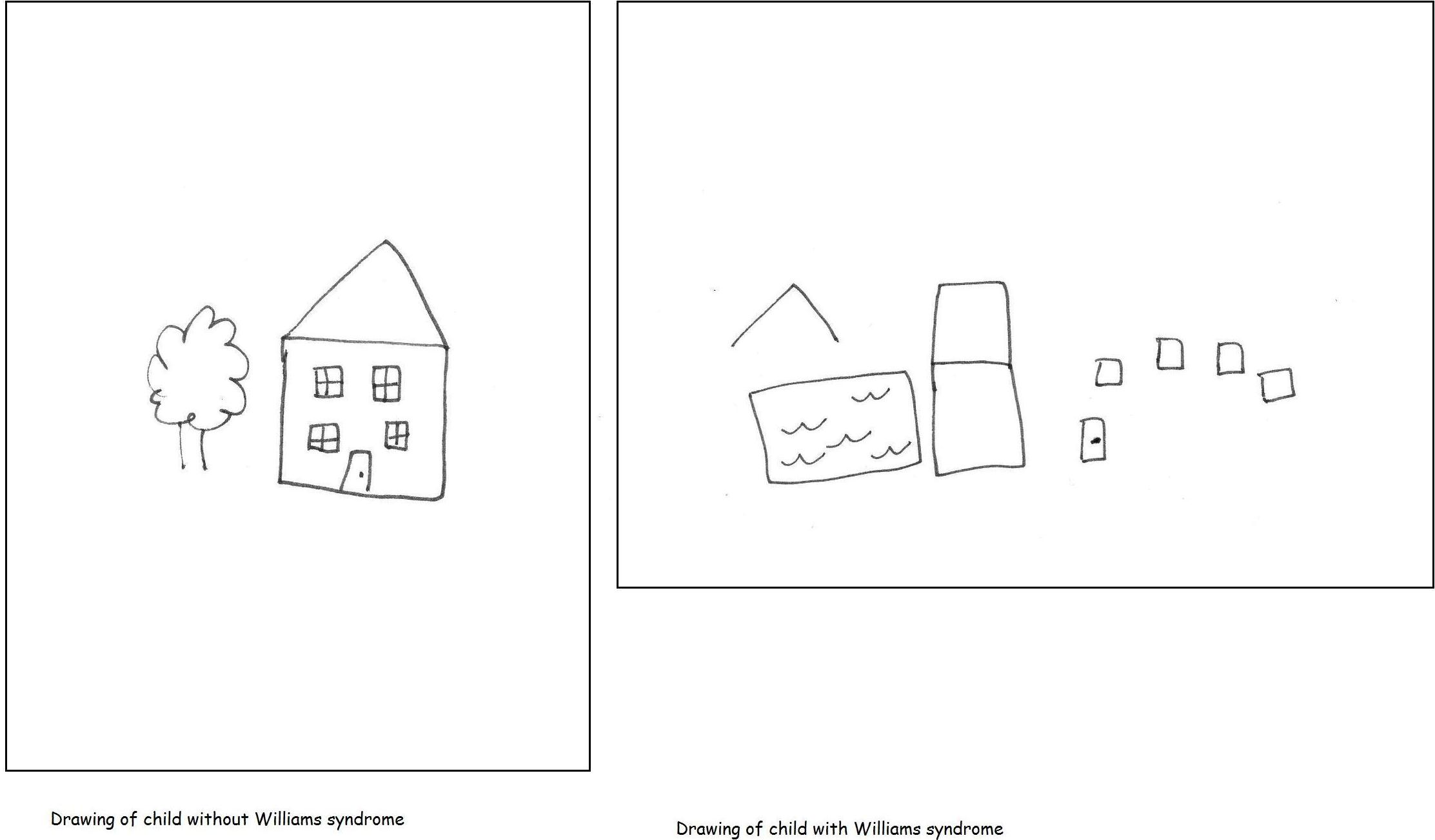

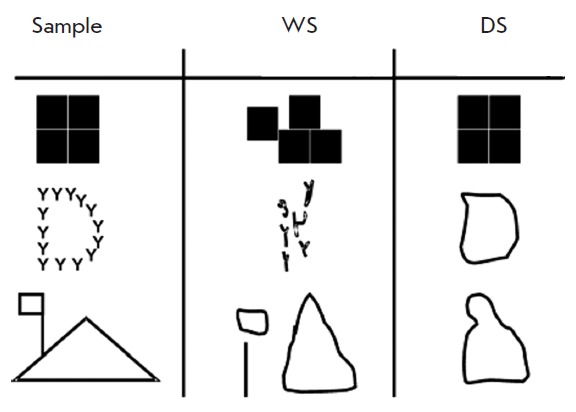

Finally, people with Williams syndrome tend to be friendly and outgoing. They typically have intellectual disabilities, which include problems with visuospatial construction. This term refers to difficulties with buttoning a shirt, drawing, or making patterns with blocks. Children asked to draw objects may draw disconnected parts of each object (see examples below). This problem may diminish as children get older (for more examples, see reference 8).

An intriguing feature of Williams syndrome is that patients may be talkative and have verbal abilities that are paradoxically good in comparison to their other cognitive problems. Although research on this trait is currently inconclusive, the chatty nature of WS patients tends to stand out to clinicians. People who know WS patients well say that they have good vocabularies, are are talkative, and are good storytellers. In addition, people with Williams syndrome tend to have a great affinity for music and many patients have what are described as excellent memories for lyrics and an excellent ability to discriminate between melody and harmony. Musicality in children with WS may not appear until after age 10. The US Williams Syndrome Association has written a summary of WS and musical ability. Finally, people with Williams syndrome may have very good auditory memories, a trait that helps them memorize song lyrics, stories, and other details. The Williams Syndrome Association notes that although learning something new may be difficult for WS patients, they tend to retain information and ideas once they have been learned (9).

An excellent overall review of Williams syndrome was published in 2008 (10). This study synthesized information from 178 previous studies.

Syndrome-specific growth charts exist for Williams syndrome. Please see our UK page for links to the charts (syndrome-specific growth charts are at the bottom of the page).

Williams syndrome is caused by a deletion in the 7q11.23 region of chromosome 7. In lay terms, this means that DNA is missing from chromosome number 7. The diagnosis is confirmed by looking for one of the genes that is normally in that region. This gene is called elastin or ELN, and the technique used to look for it is called FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization). A person without Williams syndrome has two copies of elastin. A person with WS is missing one of the copies. A list of laboratories performing the test is listed in the link at the right.

The National Institute of Mental Health has been running an observational study of people with Williams syndrome. The study is called Defining the Brain Phenotype of Children With Williams Syndrome The goal of the study is to learn about how the brain changes during childhood and adolescence in people with WS and how genes affect these changes. The study is recruiting WS patients aged 5 to 17. More information about the study, including contact information, is available at clinicaltrials.gov

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for Williams syndrome includes other conditions that cause congenital heart disease, intellectual disabilities, and growth problems.

Smith-Magenis syndrome (SMS). People with SMS may have cardiac problems, short stature, and intellectual disabilities. In addition, sensitivity to sound occurs in both conditions. The two conditions may be distinguished by the loquacity of WS patients in comparison to SMS patients, by facial appearance (including a stellate iris pattern in WS), and by behavioral problems in SMS that do not appear to occur in WS. These problems include a variety of self-injurious behaviors (face slapping, nail pulling, hand biting, insertion of objects into the body, etc.). In addition, although both syndromes are caused by deletions of genetic material, the deletions in Williams syndrome are on chromosome number 7, while those associated with SMS are on chromosome 17. Thus, genetic testing has the potential to distinguish the two syndromes.

Noonan syndrome (NS). NS patients may have congenital cardiac problems and short stature. Intelligence is normal in more than half people with NS, with some patients having mild intellectual disabilities. NS patients tend to have specific learning disabilities, which include, like WS, visual-constructional problems. Most people with NS also have a history of bruising or bleeding that is abnormal. This problem does appear to occur in Williams syndrome. Stellate iris does not appear to be a feature of NS.

The most common serious heart problem in WS is supravalvar aortic stenosis (SVAS), which affects over 60% of patients. The term SVAS refers to a narrowing of the aorta just above the aortic valve. This abnormality affects blood flow from the heart to the rest of the body (except the lungs). Alternatively, pulmonary valve stenosis (PVS) is the most common problem in Noonan syndrome (20-50% of patients, according to a GeneReviews. The term PVS refers to a narrowing of the area separating the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. The valve cannot open as widely as it should, which restricts blood flow to the lungs.

Other conditions that may be considered in the differential diagnosis for WS include autosomal dominant SVAS. Like Williams syndrome, this condition is caused by a mutation in the ELN gene. SVAS can be inherited as a single trait without the other problems and traits associated WS. It has been suggested that WS and autosomal dominant SVAS are two extremes of the same disease, but this question has not been definitively answered.

Autosomal dominant cutis laxa (ADCL) is caused by mutations in the ELN gene (as opposed to deletions of a larger area of the region on chromosome 7 where ELN is located in Williams syndrome). ADCL is characterized by loose skin, an increased risk of aortic aneurysms, and increased risk of emphysema. Although emphysema has been reported in a WS patient who was a smoker (11), emphysema does not appear to be a typical part of WS.

References

- 1. Strømme P et al. (2002) Prevalence estimation of Williams syndrome. J Child Neurol 17(4):269-271. Abstract on PubMed.

- 2. Winter M et al. (1996) The spectrum of ocular features in the Williams-Beuren syndrome. Clin Genet 49(1):28-31. Abstract on PubMed.

- 3. Sugayama SMM et al. (2003) Williams-Beuren Syndrome. Cardiovascular abnormalities in 20 patients diagnosed with fluorescence in situ hybridization. Arq Bras Cardiol 81(5):468-473. Full text from Scielo.

- 4. Collins RT et al. (2010) Cardiovascular abnormalities, interventions, and long-term outcomes in infantile Williams syndrome. J Pediatr 156(2):253-258. Abstract on PubMed.

- 5. Collins RT (2013) Cardiovascular disease in Williams syndrome. Circulation 127(21):2125-2134. Full text from publisher.

- 6. Ergul Y et al. (2012) Cardiovascular abnormalities in Williams syndrome: 20 years' experience in Istanbul. Acta Cardiol 67(6): 649-655. Abstract on PubMed.

- 7. Eronen M et al. (2002) Cardiovascular manifestations in 75 patients with Williams syndrome. J Med Genet 39:554-558. Full text on PubMed.

- 8. Nikitina EA et al. (2012) Williams syndrome as a model for elucidation of the pathway genes-the brain-cognitive functions: genetics and epigenetics. Acta Naturae 6(1):9-22. Full text on PubMed.

- 9. Williams Syndrome Association: information for teachers.

- 10. Martens MA et al. (2008) Research Review: Williams syndrome: a critical review of the cognitive, behavioral, and neuroanatomical phenotype. J Child Psychol Psychiat 49(6):576-608. Full text.

- 11. Wan ES et al. (2010) Pulmonary Function and Emphysema in Williams-Beuren Syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 152A(3):653-656. Full text on PubMed.

- 12. Hill MA et al. (2014) UNSW Embryology Wiki. This image is freely available.

- 13. Morris CA (1999) Williams Syndrome. 1999 Apr 9 Updated March 23, 2017. GeneReviews [Internet] Pagon RA et al., editors. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2017. Full text.

- Sindhar. Sindhar S et al. (2016) Hypercalcemia in patients with Williams-Beuren syndrome. J Pediatr 178):254-260. Full text on PubMed.