Angelman Syndrome (AS)

Clinical information

Angelman syndrome is a rare disease that is primarily neurodevelopmental. According to NIH's Genetics Home Reference (see link at right under General Information), AS occurs in one person in 12,000 to 20,000 people. The defining problems in this condition are neurological and developmental. In most patients, speech and motor development are severely impaired or delayed. These are usually the first clinical signs of AS in affected infants. Typically, such delays are apparent by six to twelve months of age. Patients commonly develop seizures (epilepsy) during childhood, and nearly all individuals have abnormal EEGs.

Although some people with AS have milder symptoms and may not be diagnosed until adolescence or even adulthood, nonspecific intellectual disability is usually severe even in these patients (1, 2, 4). Medications are often required during childhood to control seizure activity or sleep disturbances. Clinical features that may occur in Angelman syndrome include the following:

- Failure to develop speech

- Severe intellectual disability

- Delayed motor milestones, balance problems, falls, and/or clumsiness

- Ataxic, stiff, or unsteady wide-based gait, usually with arms flexed upright

- Seizures (of any type, or mixed types), usually developing before 8 years of age

- Sleep disturbances, inattentiveness or distractibility, with or without hyperactivity

- Friendly personality, with frequent smiling and outbursts of laughter, which may seem unprovoked or random

- Rare/absent tears or crying

- Thrusting of the tongue

- Fascination with water

- Flapping or waving motions of the hands when excited or ambulatory

- Heat intolerance/sensitivity

Neurological problems in AS

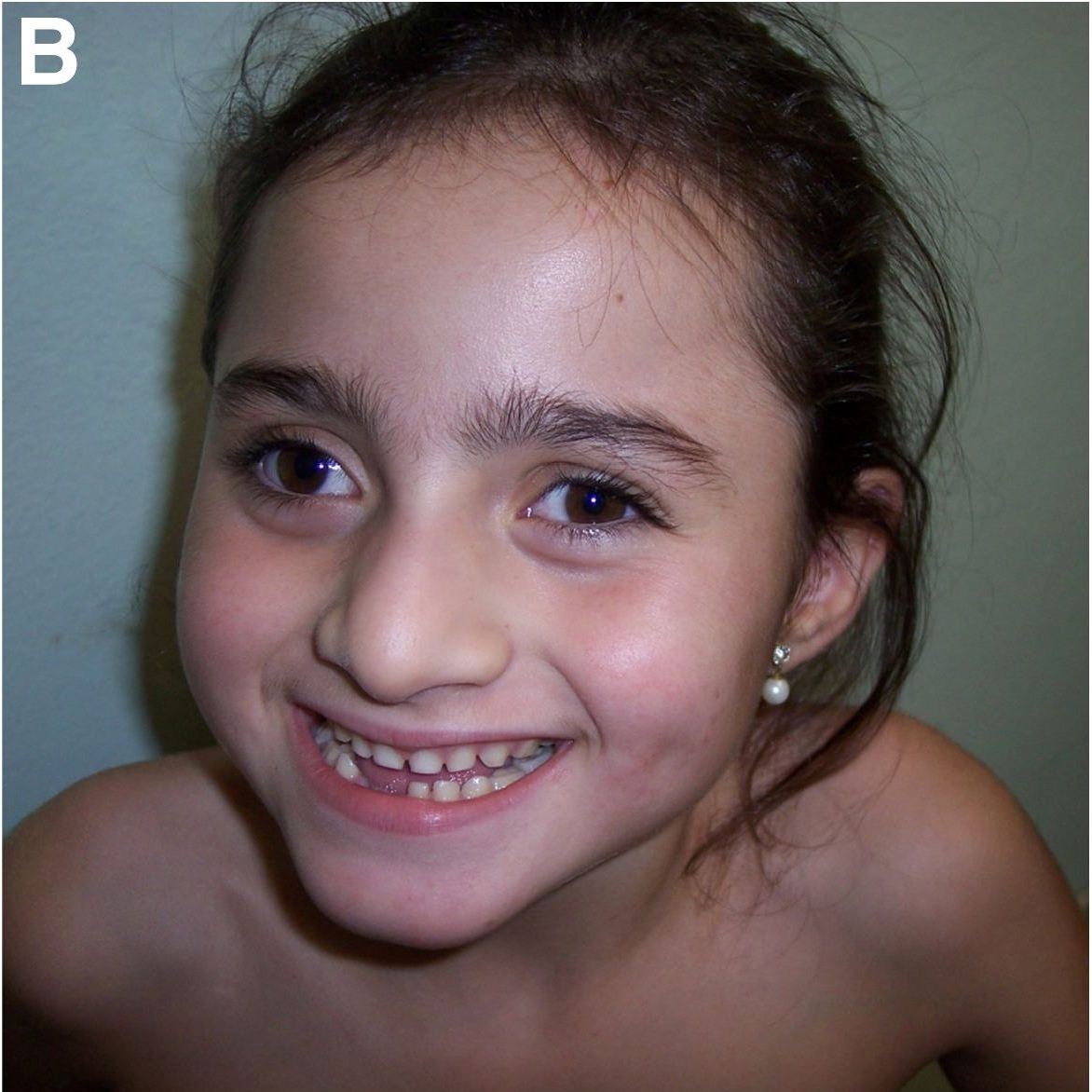

A number of non-neurological problems also occur in AS. They include widely spaced teeth, strabismus (crossed eyes), obesity in older individuals, brachycephaly/flattening of the back of the head, gastroesophogeal reflux disease (GERD), acquired (postnatal) relative or absolute microcephaly, spinal curvature abnormalities (scoliosis, kyphosis, or both), and hypopigmentation (lighter-than-expected hair, eyes, and/or skin). Macrostomia (large/wide mouth) and/or jaw prognathism are usually present, and may become more pronounced with age (2, 4). The photo at the right shows some of the facial characteristics which are typical of Angelman Syndrome; a wide mouth, widely spaced teeth, and a prominent lower jaw (5).

Genetics

Angelman Syndrome is one of a pair of diseases caused by errors in expression of the gene UBE3A, on chromosome 15. About 70% of AS patients have a deletion of the maternal copy of the gene. In others, there may be a mutation in the maternal copy of the gene, or another mechanism such as inheriting two paternal copies of the gene (paternal uniparental disomy, UPD). The syndrome occurs because the paternal gene is silenced/inactivated in certain brain regions. If the maternal copy of the gene is not present or is not functional, then there is deficient expression of UBE3A in those brain tissues. This is the cause of the range of features in AS (3).

Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) is the sister syndrome of AS. PWS is caused by the absence of functional paternal UBE3A.

Most cases of AS occur spontaneously (with no family history of the disorder), and are not likely to recur in a family. There are some cases in which a dominant maternal inheritance pattern exists, however. Genetic testing is required to rule out a heritable defect in maternal UBE3A, which can lead to 50% risk of passing the disease to an affected child's future siblings (3, 4).

Diagnosis and Testing

AS is usually suspected because of neurobehavioral features such as severe language impairment, seizures, motor delays, along with the happy personality noted above. Specific EEG features have also been associated strongly with AS, and are considered highly sensitive diagnostically. This is particularly true in infants and toddlers, where many developmental delays may not yet be strikingly apparent. Cytogenic analysis is only useful in ~1% of AS patients; these people have visible chromosome rearrangements such as translocations or inversions. Parent-specific DNA methylation analysis detects abnormalities in Chromosome 15 in about 80% of Angelman patients, but the test does not distinguish mechanism, which might be due to a deletion, paternal uniparental disomy, or an imprinting defect. Molecular genetic testing using FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) can often confirm a deletion of 15q11-13 (where the UBE3A gene lies), or paternal disomy (inheriting no maternal copy of the UBE3A gene). In about 10% of AS patients, sequencing the UBE3A gene reveals a mutation. Testing family members may help to identify heritable UBE3A mutations and provide information for genetic counseling (3). In about 10% of AS cases, no definitive genetic cause can be identified.

Differential Diagnosis

In making a diagnosis, AS should be distinguished from several disorders with very similar phenotypes (4). Infants with AS may have jerky movements or fine tremors which differentiate the condition from encephalopathy, cerebral palsy, or mitochondrial encephalomyopathy.

Mowat-Wilson Syndrome (MWS) typically presents with AS-like characteristics including developmental delays, happy demeanor, seizures, and microcephaly. MWS also occurs with congenital heart defects and possibly with congenital abnormalities of the corpus callosum, which are not characteristic of AS.

Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome (PTHS) is characterized by a wide mouth, microcephaly, seizures, an ataxic gait, and a happy personality. Frequent episodes of hyperventilation occur in PTHS, but do not typically occur in AS patients. PTHS is usually inherited via autosomal recessive or dominant mechanisms, meaning that there is often a family history of the disorder.

Christianson syndrome is an X-linked disorder which may appear clinically indistinguishable from AS, but EEG abnormalities in each disorder provide a means of differentiating between the diagnoses.

Rett Syndrome (RS). RS is a neurodevelopmental disorder that can look extremely similar to AS. One key point about RS is that patients are always girls. In addition, RS patients typically acquire motor and language skills that they they lose, while AS patients never gain these skills.

Finally, there are also some metabolic disorders which may result in an AS-like phenotype. AS does not cause metabolic abnormalities (4).

References

- 1. Williams CA et al. (2006) Angelman syndrome 2005: updated consensus for diagnostic criteria. Am J Med Genet 140A(5): 413-418. Full text from publisher.

- 2. Varela MC et al. (2004) Phenotypic variability in Angelman syndrome: comparison among different deletion classes and between deletion and UPD subjects. Eur J Hum Genet 12(12):987-992. Full text from publisher.

- 3. Ramsden SC et al. (2010) Practice guidelines for the molecular analysis of Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. BMC Med Gen 11:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-70. Full text on PubMed.

- 4. Dagli AI & Williams CA.(1998) Angelman Syndrome. Updated December 21, 2017. GeneReviews [Internet] Pagon RA et al., editors. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2021. Full text.

- 5. De Molfetta GA et al. (2012) 1031-1034delTAAC (Leu125Stop): a novel familial UBE3A mutation causing Angelman syndrome in two siblings showing distinct phenotypes. BMC Med Gen 13:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-124. Full text on PubMed.

- 6. Salehi Omran M & Bakhshandeh Bali (2010) A case report of a 2.5 year old girl with Angelman Syndrome (AS). Iran J Child Neurol 3(4):59-63. Full text from publisher.

- 7. Horvàth E et al. (2013) Early detection of Angelman syndrome resulting from de novo paternal isodisomic 15q UPD and review of comparable cases. Mol Cytogen 6:35. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-6-35. Full text on PubMed.

- 8. Fridman C & Koiffmann, CP. (2000) Genomic imprinting: genetic mechanisms and phenotypic consequences in Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Genet Mol Biol 23(4):715-724. Full text from Scielo.