Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS)

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS) are a group of 13 related conditions that affect connective tissue (1). Connective tissue is found everywhere in the body. It connects other types of tissues, separates them, and supports them. Examples of connective tissue include bone, cartilage, fat, blood, and lymphatic tissue. When connective tissue is abnormal because of a disease, a variety of problems result.

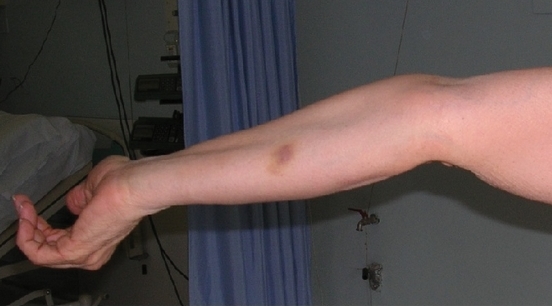

For example, certain problems happen in all of forms of EDS. The first is joint hypermobility (often called loose or double joints). People with EDS can often move their joints in ways that are impossible for most unaffected people. The photograph at the bottom of this page has an example (note that many people without EDS have loose joints, so having joint hypermobility does not mean that you have EDS). The second thing that happens in every type of EDS is stretchy (hyperextensible) skin. This feature is nearly universal in some types of EDS (such as type 1, the classical form). In our literature survey, we found that stretchy skin occured in less than half of people with the hypermobile and vascular forms, more than half of patients with the periodontitis type, and in a large majority of people with the arthrochalasia type (>80%).

Many forms of EDS happen because of mutations in genes that make collagen, which can be thought of as both holding the body together and strengthening it. Collagen gives structure to muscles, tendons, skin and bones. In most people, it is abundant in these tissues. In people with EDS, collagen may not be as strong as it should be, or there may not be enough of it. For example, skin and joints may be loose because they don't have enough collagen to hold them together securely, or because the collagen they have is weaker than it should be.

Doctors and other medical professionals assess joint hypermobility with a scoring system called the Beighton score, which was developed in the early 1970s (2). This simple system scores your ability to move a joint past certain angles. The highest score is 9 points, and higher scores mean greater joint hypermobility. Generally speaking, scores of 4 or higher (at any time, past or present) indicate joint hypermobility. Many EDS patients have scores of 8 or 9, although many have lower scores, and a minority do not have hypermobile joints. Interested readers may wish to see a basic description of the scale with a video and photos or a more technical description.

Joint hypermobility puts EDS patients at high risk for joint dislocations and partial dislocations (called subluxations). These problems can be painful, and in some cases, debilitating. Surgical procedures have been used to improve skeletal stability and improve quality of life; for examples and reviews, see references 3-5. However, experts tend to agree that non-surgical options should always be exhausted first, and careful discussions with doctors are important in this decision.

Tissue fragility is another common feature of EDS. This problem is very serious in the vascular type of EDS (vEDS). The type of collagen affected in vEDS plays a role in supporting blood vessels. When the integrity of their support system is affected, blood vessels can rupture spontaneously. This problem is especially dangerous because it affects medium and large blood vessels, as well as small ones. It also affects the bowel. Surgery on a person with vEDS must be performed with great care in order to avoid serious complications. This problem may also happen in kyphoscoliotic EDS (kEDS), but it is less common than in vEDS. Alternatively, while people with the hypermobile form (hEDS) are also prone to blood vessel ruptures, ruptures tend to occur in the small blood vessels. Tissue fragility can also lead to hernias and problems in pregnancy. Fragile skin is also a common manifestation of EDS, especially in people with the classic, kyphoscoliotic, and periodontitis types.

Tissue fragility in EDS can also lead to hernias and problems in pregnancy. Fragile skin is also a common manifestation of EDS, especially in people with the classic, kyphoscoliotic, and periodontitis types.

A new classification system for EDS was released in 2017 (1). It's called the 2017 International Classfication for the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes. This new system names 13 different subtypes of EDS. It relies primarily on descriptive terms for different types of EDS (e.g. vascular EDS, meaning that it affects blood vessels prominently). Two other systems existed before this one. They were named Villefanche [1998] and Berlin [1988]. Both systems used names and numbers. The numbers in the new system are different from the old ones, and we've included the old ones here. Advances in genetics have allowed to researchers to find genes that cause different subtypes of EDS, which has allowed them to separate the old classic subtype (numbered 1 & 2) of EDS into 2 different subtypes.

- 1. Classical EDS (cEDS; formerly type 1/2)

- 2. Classical-like EDS (cEDS; formerly type 1/2)

- 3. Cardiac-valvular (cvEDS)

- 4. Vascular (vEDS)

- 5. Hypermobile (hEDS; formerly type 3)

- 6. Arthrochalasia (aEDS; formerly type 7a/b)

- 7. Dermatosparaxis (dEDS; formerly type 7c)

- 8. Kyphoscoliotic (kEDS; formerly type 6)

- 9. Brittle Cornea syndrome (BCS)

- 10. Spondylodysplastic (spEDS)

- 11. Musculocontractural (mcEDS)1

- 12. Myopathic (mEDS); type 12

- 13. Periodontal (pEDS; formerly type 8)

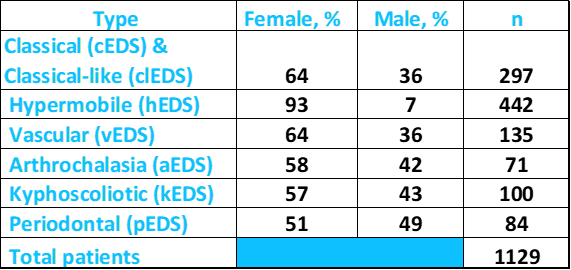

EDS affects women more commonly than men. In the literature survey we did for our analytics tool, we counted the number of male and female patients while we were characterizing in six different types of EDS. Altogether, we analyzed data from ~1,200 patients. Sex information was available for ~1,100. The table below shows that although more EDS patients are women in each type of EDS, the female:male ratio varied between each type. For example, females dominated the individuals reported with the hypermobility type, while males comprised a substantial minority of kyphoscoliotic and arthrochalasia patients. The distribution was roughly even in the periodontal type. However, the low number of case reports for these three types of EDS may have affected the outcome of this small analysis.

Above: Percentages of male and female patients with different types of EDS. Source: FDRF via published literature.

According to NIH's Genetics Home Reference (see link at right), the prevalence of all forms of EDS is roughly 1 in 5,000 worldwide. The hypermobility type (hEDS) is the most common form of EDS, and although exact figures are not known, the Gene Review article estimates that its prevalence is underestimated due to difficulites with diagnosis, and that it may occur in one person per 5,000 to 20,000.

Clinical information

hEDS is considered to be the mildest form of EDS. Its most striking features are joint hypermobility (see photo at the right) and joint pain (arthralgia). Pain may be out of proportion to what would be suggested by clinical findings. Additionally, hEDS is more common in women than men. This fact may be related to sex-specific differences in the perception of pain and joint stability rather than an absence of disease in men per se (6). This uncertainty has not been fully resolved.

The skin in hEDS patients is not as stretchy/hyperextensible as it is in patients with other forms of EDS. This fact may be helpful in diagnosis. In addition, piezogenic papules under the skin also occur in hEDS. Piezogenic papules are fat-filled skin elevations that form when pressure is applied. They often occur in the feet. The photograph at the bottom of the page shows piezogenic papules that appeared in an hEDS patient after compression was applied to her wrists.

There does not appear to be a distinctive facial appearance associated with hEDS. The most common signs and symptoms of this condition are as follows:

- Joint hypermobility

- Joint dislocations or subluxations (see photo below)

- Joint and/or muscle pain and/or headaches

- Mildly stretchy skin that appears normal after being released

- Smooth, velvety skin

- Fragile skin that may scar abnormally and/or easy bruising

- Fragile blood vessels (especially capillaries) that are prone to rupturing

- Poor balance and/or fear of falling

- Clumsiness

- Inability to stand for long periods

- Flat feet

- Trouble concentrating

- Absent frenulum below the tongue (a tissue that anchors the tongue to the lower jaw)

- Functional bowel disorders (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome)

Signs and symptoms of hEDS

A condition called joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS) is very similar to hEDS, and many researchers consider them to be the same condition (7,8). This opinion is not shared universally, although sources such as Orphanet (see link at right) list JHS as being a synonym for the term hEDSypermobility. This question will be answered definitively when one or more genes is associated with hEDS.

Diagnosis and Testing

hEDS is an autosomal dominant disorder. This term means that hEDS is usually passed from one affected parent to a child. However, it can also occur sporadically in a family without an affected parent. Mutations in a gene called tenascin B (TNXB) cause hEDS in a small number of cases (9,10). However, apart from this gene, researchers have not identified the gene or genes responsible for the vast majority of hEDS cases. As a result, at this time, and the diagnosis is still clinical. The link at the right provides information about labs that test for mutations in TNXB.

It is important to remember that there is a lot of overlap between the different forms of EDS. This fact means that, in the absence of laboratory testing, accurate subcategorization of EDS in a patient may be difficult or even impossible. This fact is especially true of hEDS, given the lack of genes associated with it.

Major and minor criteria for diagnosing hEDS were established as part of the 2017 classification system (1). The criteria are lengthy and detailed given 1) the variation in hEDS and 2) the continued lack of information about genes associated with hEDS. Interested readers should consult reference 1 for more information.

Differential Diagnosis

Other forms of EDS. The differential diagnosis for hEDS includes all the other forms of EDS. Mild forms of classic EDS (types 1 and 2) are most similar to hEDS, and diagnoses of hEDS are sometimes changed to EDS-Classic. Most EDS-classic patients have mutations in the genes COL5A1 or COL5A2, which encode type 5 collagen, although COL1A2 is mutated in a minority of cases. Together, the hypermobility and classic forms of EDS are estimated to make up ~80% of all EDS cases (11).

The vascular form of EDS (formerly called Sack-Barabas syndrome) deserves special consideration in this context. vEDS patients are prone to ruptures of large blood vessels; these ruptures may be fatal. Because surgical management of any EDS patient is a possibility, clinicians may wish to rule out vEDS in a person suspected of having EDS. All cases of vEDS are caused by mutations in the gene COL3A1.

Overall, joint hypermobility occurs in a variety of medical conditions, and many people without a medical condition have lax joints. In fact, when not part of a disorder, hypermobile joints confer an advantage in sports such as gymnastics and ice skating, as well as in certain forms of dance.

Marfan syndrome. Most medical conditions involvong lax joints are relatively easy to distinguish from EDS, but some are not. Marfan syndrome is an example. Like EDS, Marfan syndrome is a connective tissue disorder and patients have lax joints. Marfan patients generally have a body type called a Marfanoid body habitus. This term means that a person is tall and slender, with long arms, hands, fingers, legs, feet and toes. A Marfanoid body habitus occurs in a minority of hEDS patients, but it does not appear to be generally associated with classic EDS. The Marfan Foundation has many photographs of Marfan patients of different ethnicities. Unlike EDS patients, Marfan patients do not appear to have fragile skin and blood vessels.

Cutis laxa. Superficially, the stretchy skin found in most forms of EDS may be confused with cutis laxa type 1 and type 2, as stretchy skin is also a feature of these conditions. However, the skin in cutis laxa patients tends to sag and does not return to its normal position after being extended. Cutis Laxa patients often have a prematurely aged appearance.

Williams syndrome. The Gene Review on classic EDS (see link at right) has a list of other conditions that are part of the differential diagnosis for EDS. They include , which may be distinguished from classic EDS by specific intellectual disabilities, a specific personality type, and other factors. The list of conditions also includes Loeys-Dietz syndrome, Stickler syndrome, and a number of other conditions.

References

- 1. Malfait F et al. (2017) The 2017 International Classification of the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes Am J Med Genet C 175(1):8-26. Abstract on PubMed.

- 2. Beighton P et al. (1973) Articular mobility in an African population. Ann Rheum Dis 32(5):413-418. Full text on PubMed.

- 3. Cole AS et al. (2000) Recurrent instability of the elbow in the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. A report of three cases and a new technique of surgical stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 82(5):702-704. Full text from publisher.

- 4. Weinberg J et al. (1999) Joint surgery in Ehlers-Danlos patients: results of a survey. Am J Orthop 28(7):406-409. Abstract on PubMed.

- 5. Shirley ED et al. (2012) Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in orthopaedics. Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment implications. Sports Health 4(5):394-403. Full text on PubMed.

- 6. Castori M et al. (2010) Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type and the excess of affected females: possible mechanisms and perspectives. Am J Med Genet A 152A(9):2406-2408. Abstract on PubMed.

- 7. Tinkle BT et al. (2009) The lack of clinical distinction between the hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and the joint hypermobility syndrome (a.k.a. hypermobility syndrome). Am J Med Genet A 149A(11):2368-2370. Abstract on PubMed. Full text from EDNF.

- 8. Castori M et al. (2012) Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type: an underdiagnosed hereditary connective tissue disorder with mucocutaneous, aand systemic manifestations? ISRN Dermatology Volume 2012:Article 751768. doi: 10.5402/2012/751768. Full text on PubMed.

- 9. Schalkwijk J et al. (2001) A recessive form of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome caused by tenascin-X deficiency. N Engl J Med 345:1167-1175. Full text from publisher.

- 10. Zweers MC et al. (2003) Haploinsufficiency of TNXB Is Associated with Hypermobility Type of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 73(1):214-217. Full text on PubMed.

- 11. Beighton P (1993) The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. McKusick's Heritable Disorders of Connective Tissue (5th edition; ed. Peter Beighton); Mosby, St. Louis, Chapter 6; pages 216-217.